How nerve cells control misfolded proteins

neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington’s or Parkinson’s disease are associated with misfolded and aggregated proteins. Researchers have discovered a new mechanism used by cells to protect themselves.

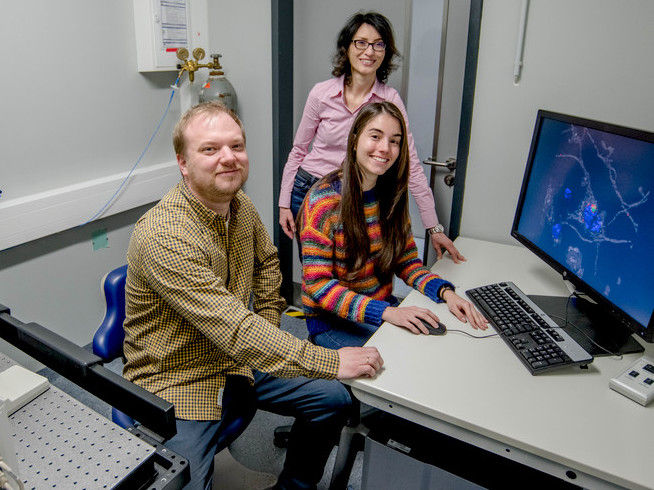

Dr. Verian Bader and Ana Sánchez Vicente are members of the research team headed by Professor Konstanze Winklhofer (in the background) which has revealed a new role of the protein complex Lubac.

© RUB, Marquard

Researchers have identified a protein complex that marks misfolded proteins, stops them from interacting with other proteins in the cell and directs them towards disposal. In collaboration with the neurology department at the Ruhr-Ubiversität’s St. Josef-Hospital as well as colleagues at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried, an interdisciplinary team under the auspices of Professor Konstanze Winklhofer at Ruhr-Universität Bochum has identified the so-called Linear Ubiquitin Chain Assembly Complex, Lubac for short, as a crucial player in controlling misfolded proteins in cells.

The group is hoping to find a new therapeutic approach to treat neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or Huntington’s chorea, all of which are associated with misfolded proteins.

New function of protein complex

Earlier studies have revealed that the protein complex Lubac regulates signalling pathways of the innate immune response that are mediated by the transcription factor NF-kB. For example, Lubac can be recruited to trigger immune responses by binding to bacteria in the cells and activating NF-kB.

“Our study revealed that the Lubac system has a previously unknown function,” says Konstanze Winklhofer, who is also member of the Cluster of Excellence Ruhr Explores Solvation, Resolv for short. “It appears that Lubac recognises misfolded proteins as dangerous and marks them with linear ubiquitin chains, thus rendering them harmless to nerve cells.” Unlike its response to bacteria, this function of Lubac is independent of the transcription factor NF-kB.

Aggregates of misfolded proteins are toxic to cells, because they interfere with various processes. For example, they expose an interactive surface thereby sequestering and inactivating other proteins that are essential for the cell. This process disrupts the function of nerve cells and can cause cell death.

Preventing protein interactions

The research team has now decoded the mechanism described above using the huntingtin protein, the misfolding of which causes Huntington’s disease. By attaching linear ubiquitin chains to aggregated huntingtin, the aggregates are shielded from unwanted interactions in the cell and can be degraded more easily. In Huntington’s patients, the Lubac system is impaired, as the team demonstrated.

These insights were gained by combining cell biology and biochemistry methods and using high-resolution microscopy (Structured Illumination Super-Resolution Microscopy).

Mechanism works for various proteins

The protective effect of Lubac is not limited to huntingtin aggregates. The researchers also detected linear ubiquitin chains attached to protein aggregates that play a role in other neurodegenerative disorders, for example in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

“The attachment of linear ubiquitin chains is a highly specific process, as there is only one protein – namely a Lubac-component – that can mediate it,” explains Konstanze Winklhofer. “Based on these insights, strategies for new therapeutic approaches could be developed.”

In future studies, the team intends to identify small molecules that affect linear ubiquitination and to test if they have any positive effects on neurodegeneration. “But there is still a long way ahead until a drug can be developed,” concludes Konstanze Winklhofer.