Brain Loses the Beat: Aging Changes the Fine-Tuning of Neuronal Rhythms During Sleep

Study unveils the link between altered coupling of neuronal rhythms and forgetting

Advertisement

Our brain is at work non-stop, day and night. While we are sleeping it ensures that our experiences during the day are retained permanently in our memory. This process is called consolidation. Consolidation requires that slow rhythmic patterns of neuronal activity are as precisely coupled with rapid patterns as possible, especially during deep sleep. Together with colleagues from Goethe University Frankfurt and the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, a research team at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development has now been able to show that this coupling is no longer in step in older people who forget more. The findings of the study, which involved 34 younger and 41 older participants, has been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

The brain is not only active when we are awake, but also when we are asleep. When we are awake, the interplay of the different brain regions ensures that we can orient ourselves in the world, carry out actions, and perceive the environment. During sleep, our experiences are sifted, ordered, and stabilized (or forgotten). This is why sleep is essential for the long-term storage and interconnection of newly acquired knowledge, and thus for learning.

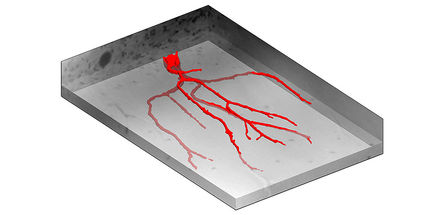

Temporally fine-tuned communication between the hippocampus and the cerebral cortex is central for information exchange during sleep. The hippocampus is a structure deep in the brain that is crucially involved in the rapid, but short-term storage of newly acquired knowledge und everyday experiences. Sleep enables the hippocampus to “train“ the more slowly learning cortex by repeatedly reactivating and gradually laying down newly learned content. In order to be successful, this “training” of the cortex requires temporally precise coordination of neuronal activity in the brain regions involved.

“By observing the brain activity of sleeping participants, we were now able to show that people who forget more distinguish themselves from others in one important aspect: The activity of neurons in the hippocampus and the cortex is less precisely coupled in more forgetful people,” says Beate Muehlroth, first author of the study and doctoral student at the Center for Lifespan Psychology of the Max Planck Institute for Human Development.

Researchers can visualize brain activity during sleep using electroencephalography (EEG). EEG measures the electrical fields generated by neurons whose rhythmic activity patterns are characteristic during phases of wakefulness and sleep respectively. The most striking feature of phases of deep sleep are slow rhythms of about 0.5 to 4 oscillations per second that spread across almost the entire cortex. These so-called “slow waves” enable the coordination of neuronal information processing across large parts of the brain. They open time windows during which memories can be reactivated by the hippocampus and optimally learned by the cortex.

In the human EEG, the activation of the information exchange between the hippocampus and the cortex is characterized by fast rhythmic neuronal activity with a frequency of 12 to 16 oscillations per second. These oscillation patterns resemble spindles like those used to spin wool and are therefore called “sleep spindles.” Optimal “training” of the cortex by the hippocampus is possible when the sleep spindles occur precisely at those time points when the slow waves have prepared the neurons of the cortex for efficient information processing.

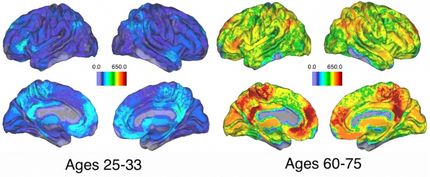

The research team examined the learning and memory performance of 34 younger participants aged 19–28 years and 41 older participants aged 63–74 years in a memory test developed specifically for this purpose. The participants spent the night between learning and the memory test on the following day at home. The neuronal activity during sleep was measured with a portable sleep EEG system. In addition, the size and structure of memory- and sleep-relevant brain regions was assessed using magnetic resonance tomography (MRT) in the lab.

As expected, the results revealed that on average, older participants forgot more than younger participants did. Additionally, participants with lower levels of memory performance were found to show less precise coupling between sleep spindles and slow waves during phases of deep sleep. Like a person not quite clapping on the beat, the sleep spindles missed the optimal point in time to “train” the cortex, so that consolidation of the newly learned content was less successful.

“We found that the coupling of both neuronal rhythms tends to decrease while forgetfulness increases with aging. This also means that those among the older participants who did well in the memory test also showed a coupling pattern that resembled that of the younger participants,” says Markus Werkle-Bergner, senior author and project leader at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development.

In further analyses the research team was also able to show that the extent of coupling between sleep spindles and slow waves is related to the structure of those brain regions that are involved in their production. This mainly applies to the hippocampus, to a region in the frontal part of the brain called the medial prefrontal cortex, as well as the thalamus. These three regions are particularly strongly affected by aging processes. This suggests that the aging of sleep- and memory-relevant brain areas impairs processes of long-term storage of new memory contents. Future longitudinal studies will examine more closely to what extent age-related changes of sleep behavior and physiology influence the structural aging of the brain or whether the latter are causally responsible for observable sleep disturbances at older ages.