Fierce competition between the human immune system and bacterial pathogens

New insights into the recent development of the human immune system

Advertisement

Cell biologists from the University of Konstanz shed light on a recent evolutionary process in the human immune system and publish their findings in the scientific journal “Current Biology”. Facilitated by public genome data this work provides evidence that genetic alterations in the receptor molecule CEACAM3 are linked to the ability to defend against particular pathogenic microbes.

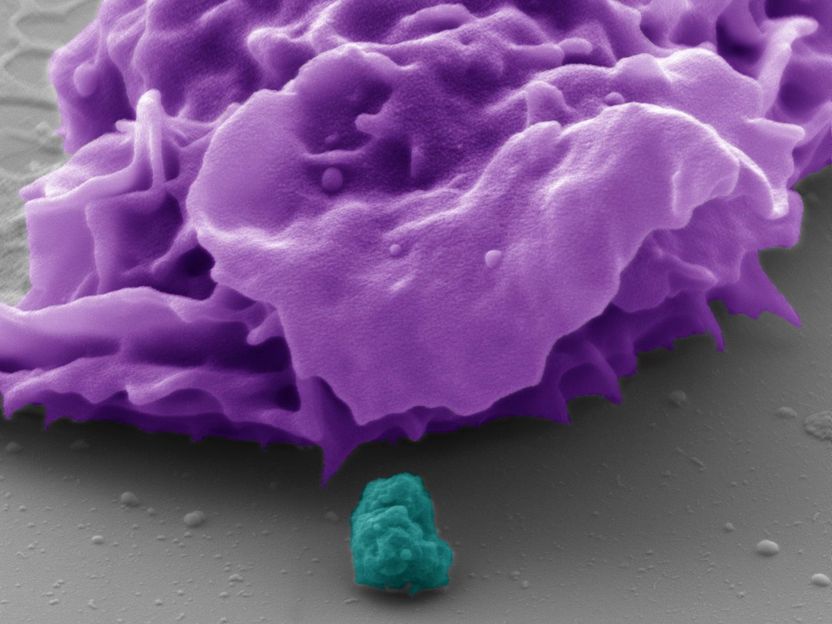

The pseudocolored electron microscope image shows a human phagocyte (purple) and a bacterium (turquoise). With the aid of the CEACAM3 receptor investigated, the phagocyte is able to detect and destroy the bacteria, which are about one micrometre in size.

Electron Microscopy Centre, Department of Biology, University of Konstanz, Dr. M. Laumann; Prof. Dr. C. R. Hauck

Like professional burglars for their clandestine activities, bacterial pathogens also need the right tool set to sneak in and establish themselves in our bodies. In this regard, some microbes are extreme specialists that infect only a single host organism. This small group includes the gonococcus and the pathogen Haemophilus influenzae, which are found only in humans. Both these pathogens share the ability to outmanoeuvre various defence mechanisms of the human body in order to attach themselves to the mucous membranes.

As recent work from the laboratory of Professor Christof Hauck, cell biologist at the University of Konstanz, now shows, our body is not helpless against these highly specialised bacteria either. A receptor, which specifically recognizes and destroys pathogens such as gonococci, is found on phagocytes of our immune system. Surprisingly, this specialized pathogen detector, named CEACAM3, exists only in humans and in our closest relatives in the animal kingdom, such as chimpanzees, gorillas and rhesus monkeys: Jonas Adrian and Patrizia Bonsignore from Christof Hauck’s group screened the genomes of various primate species for the presence of CEACAM3. They could find a CEACAM3-like receptor only in more highly evolved apes, but not in lemurs or other basal monkeys.

“This finding suggests that this receptor molecule emerged only relatively recently in the evolutionary history of primates,” says Hauck. Comparison of this receptor between various great apes furthermore revealed that CEACAM3 evolves surprisingly fast. This rapid development can be explained by the function of the receptor as a defence against specialized bacteria: Any change on the bacterial surface that allows the pathogen to escape this immune surveillance will be matched, in the course of generations, by a corresponding change in CEACAM3. “The result is a kind of molecular arms race, in which sometimes the microbes have the edge, and sometimes the immune system has,” explains Christof Hauck.

A look at the global diversity of CEACAM3 shows that we are in the midst of an ongoing competition here. “In some human populations, for example on the African continent, variants of this receptor exist. This detailed insight into the genomes of human populations has been made possible only through global data collection in recent years,” explains Jonas Adrian. With the function of CEACAM3 in mind, it was reasonable to assume that these CEACAM3 variants have the potential to detect and eliminate additional pathogens. To put this assumption to the test, Adrian and Bonsignore conducted binding studies with variants of the receptor and various bacterial pathogens. First, they modified the regular CEACAM3 molecule according to the variants found in particular human populations. Then, they produced these variants in the laboratory and specifically brought them into contact with various pathogens to analyse their binding. With this approach, the scientists were able to demonstrate that these CEACAM3 variants detect additional pathogens, including Haemophilus influenzae. So while most people can control specialized pathogens with the help of CEACAM3, people with a CEACAM3 variant are able to hold an even wider range of bacteria at bay.

The ongoing competition between humans and microbes impressively demonstrates how the mechanisms of evolution have shaped the human genome as well. The unusually rapid development of CEACAM3 indicates that such a precision pathogen detector was advantageous for our primate ancestors to hold their ground against highly specialized pathogens.