First genetic switch for C. elegans developed

Novel inducible disease model for Huntington’s disease

Advertisement

With their first ever RNA-based inducible system for switching on genes in the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), two researchers from the University of Konstanz have closed a significant gap in the research on and usage of genetic switches. The new approach was developed as part of a joint research project carried out by Dr Martin Gamerdinger (Department of Biology) and Professor Jörg Hartig (Department of Chemistry) within the University of Konstanz’s Collaborative Research Centre 969 “Chemical and Biological Principles of Cellular Proteostasis”, which is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). By sharing their respective expertise in the area of C. elegans and the development of RNA-based genetic switches, the researchers were able – for the first time – to successfully induce a gene in the animal model using an RNA-based genetic switch. They were further able to establish a novel inducible disease model for Huntington’s disease which opens up new opportunities for research and application.

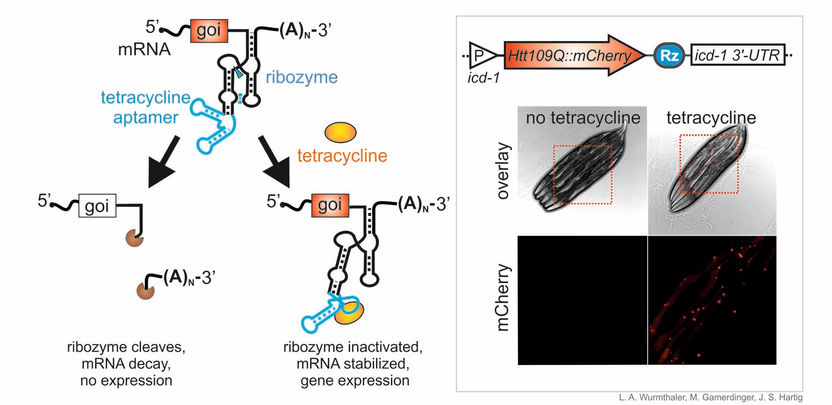

Left: How the ribozyme-based genetic switch works. A self-cleaving tetracycline-dependent ribozyme results in mRNA decay and down-regulation of gene expression. Adding tetracycline inhibits ribozyme activity, which stabilizes the mRNA and induces gene expression. Right: Application of the genetic switch in the animal research model C. elegans. Tetracycline-induced expression of the fluorescence (mCherry)-tagged Huntingtin protein (Htt) with an abnormally long polyglutamine sequence that causes Huntington's disease in humans. Htt aggregates, which are typical of Huntington's disease, can be observed to form in the animal model.

Copyright: L. A. Wurmthaler, M. Gamerdinger, J. S. Hartig

The nematode C. elegans is widely used for research in cell and developmental biology and as a model system to study human diseases. This research animal model enjoys particular popularity because its anatomy is extremely simple, because its transparency allows live cell microscopy and because many of its genes are evolutionarily conserved in humans. “However, what I found quite frustrating is that we did not have an inducible system for this animal model allowing us to switch on genes at will”, explains Dr Martin Gamerdinger, initiator of the research collaboration and project leader in CRC 969 “Chemical and Biological Principles of Cellular Proteostasis” at the University of Konstanz. As a result of the close collaboration with the Chemical and Synthetic Biology of Nucleic Acids team led by Professor Jörg Hartig, Gamerdinger and his colleagues were able to establish a particularly convenient and efficient system for inducing a gene in the C. elegans animal model.

Professor Hartig’s team, which also includes Dr Lena Wurmthaler, first author of the paper, investigates unusual structures and characteristics of nucleic acids, particularly catalytically active ribozymes and so-called riboswitches, which can be used to switch individual genes on or off. A main purpose of RNA (ribonucleic acid) in biological cells is to translate genetic information into proteins; as mRNA it serves as an information carrier. Introducing self-cleaving ribozymes to mRNA molecules leads to mRNA decay and, ultimately, gene deactivation. However, the ribozyme’s activity – and thus gene expression – can be controlled by means of ligand-dependent ribozymes. The researchers’ inducible system is based on the ligand tetracycline, which belongs to the group of antibiotics. Tetracycline binds to the RNA molecule via a so-called RNA aptamer and inhibits ribozyme activity. This, in turn, stabilizes the mRNA, which is then translated into protein. As a result, the desired gene can be switched on. “What’s so fabulous about the new genetic switch is that it can be used in all developmental stages of C. elegans, i.e. across all larval stages and in the adult animal, which was not possible until now”, explains Dr Lena Wurmthaler. Among the major advantages of this new approach is that no additional regulatory proteins are required to regulate gene expression: All that is needed to switch on the gene is to insert the ribozyme along with the aptamer (aptazyme or ligand-dependent ribozyme) into the mRNA and to feed C. elegans tetracycline. Lena Wurmthaler: “We need very little coding space and no additional expressed protein factors at all. In a single step, we can convert any gene of interest in a tetraycycline-inducible gene”.

Supported by doctoral researchers Monika Sack and Karina Gense, Martin Gamerdinger and Lena Wurmthaler were able to verify their new system by switching expression of the red fluorescence protein mCherry in various cell types of C. elegans. “Having such a simple and highly effective inducible system is a major step forward for the entire C. elegans field”, concludes Gamerdinger. The two researchers expect their new system to be relevant in a range of contexts, especially in medical research. By successfully switching on a mutant gene that encodes the Huntingtin protein (Htt) and causes Huntington’s disease in humans, a neurodegenerative disease of the brain, they were able to establish and investigate a new inducible disease model as part of their study.

As opposed to a healthy gene, the Huntingtin gene variant used in the study encodes an abnormally extended polyglutamine sequence. For their experiment, the two researchers created a particularly aggressive disease model with 109 sequential polyglutamines (Htt109Q). Demonstrably, feeding the worms tetracycline led to increased Huntingtin aggregation in C. elegans, which caused paralysis and, when targeted specifically to neurons, severe loss of motor coordination, which documents the neurotoxicity of the induced gene. Using this approach, Martin Gamerdinger and Lena Wurmthaler were able to establish the first inducible model of Huntington’s disease in C. elegans. Since it is now possible to induce toxic proteins such as Huntingtin at will, it will be possible in the future to generate and investigate additional disease models that are based on extremely toxic proteins.