Breakthrough in the investigation of feared pathogens

Researchers uncover camouflage strategy of multi-resistant bacteria

Researchers at the University of Tübingen and the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) have achieved a breakthrough in the decoding of multi-resistant pathogens. The team led by Professor Andreas Peschel and Professor Thilo Stehle was able to decode the structure and function of a previously unknown protein used by dreaded pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus like a magic cloak to protect themselves against the human immune system.

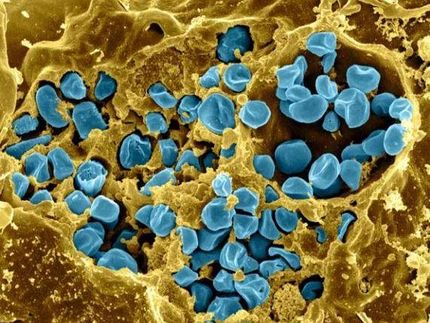

MRSA bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus) make themselve invisible to the immune system with the help of a protein.

Fotolia/crevis

Infections caused by bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus cause many deaths worldwide. Staphylococcus aureus strains resistant to the antibiotic methicillin (MRSA for short) are particularly feared in hospitals. According to a study published at the beginning of November, there were around 670,000 diseases caused by multi-resistant pathogens in the EU alone in 2015 and 33,000 patients died.

Normally, our immune system copes well with pathogens such as bacteria or viruses. However, sometimes the defensive strategies of the human body fail, especially in immunocompromised patients. Most antibiotics are meanwhile ineffective against resistant pathogens. Effective replacement antibiotics and a protective vaccine against MRSA are not yet in sight. A precise understanding of the defense mechanisms could therefore lead to new therapies against the bacteria.

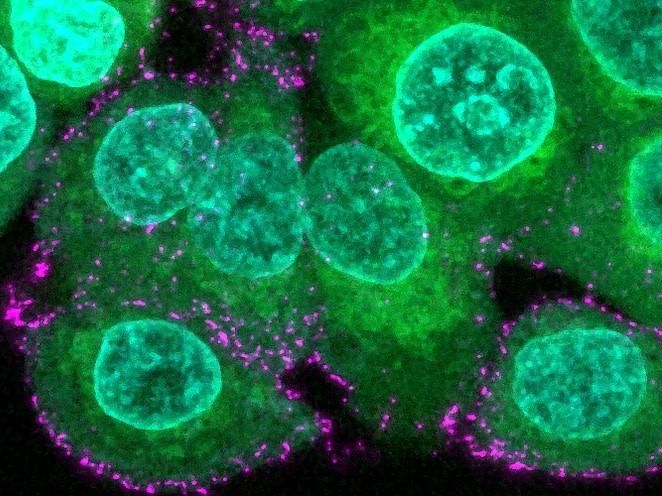

Researchers at the University of Tübingen have now described how MRSA bacteria become invisible to the immune system. They were able to show that many of the particularly frequent MRSA bacteria have acquired a previously unknown protein that prevents the pathogens from being detected by antibodies. The Tübingen scientists gave the protein the name TarP (short for teichoic acid ribitol P).

"TarP alters the pattern of carbohydrate molecules on the pathogen surface in a so far unknown way," explained Professor Andreas Peschel from the Interfaculty Institute of Microbiology and Infection Medicine at the University of Tübingen. "As a result, the immune system is unable to produce antibodies against the most important MRSA antigen, teichoic acid," said Peschel. “The immune system is ‘blinded’ and loses its most important weapon against the pathogen.”

Reprogrammed by phages

The researchers from Tübingen assume that the bacterial camouflage is the result of an exchange between the pathogens and their natural enemies, known as bacteriophages. Phages are a class of viruses that attack bacteria, use them as host cells and feed on them. In this case, phages seem to have reprogrammed their host using the TarP protein and thus altered the surface of the bacterium.

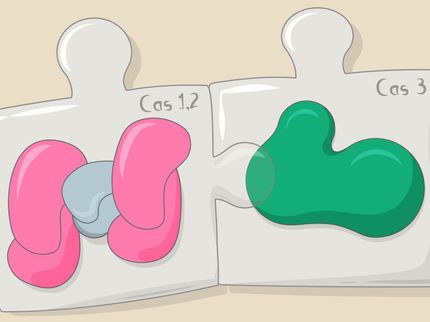

The first authors of the study, David Gerlach and Yinglan Guo, succeeded in clarifying the mechanism and structure of TarP. "We now have a detailed understanding of how the protein functions as an enzyme on the molecular level," said Gerlach. The structure-function analysis of TarP forms an excellent basis for the development of new drugs that block TarP allowing the immune system to detect the pathogens. An interdisciplinary approach, involving scientists from Denmark, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands and South Korea, was particularly important for the success of this work.

"The discovery of TarP came as a complete surprise to us. It explains very well why the immune system often has no chance against MRSA," said Professor Thilo Stehle from the Interfaculty Institute of Biochemistry. "The results will help us to develop better therapies and vaccines against the pathogens." Peschel referred to the recently approved Tübingen Cluster of Excellence "Controlling Microbes to Fight Infections" and the close cooperation with the German Center for Infection Research: "These outstanding networks will help us to further advance the research of MRSA and TarP."