A new path through the looking-glass

Innovative experimental scheme can create mirror molecules

Exploring the mystery of the molecular handedness in nature, scientists have proposed a new experimental scheme to create custom-made mirror molecules for analysis. The technique can make ordinary molecules spin so fast that they lose their normal symmetry and shape and instead form mirrored versions of each other. The research team from DESY, Universität Hamburg and University College London around group leader Jochen Küpper describes the innovative method in the journal Physical Review Letters. The further exploration of handedness, or chirality (from the ancient Greek word for hand, “cheir”), does not only enhance insight in the workings of nature, but could also pave the way for new materials and methods.

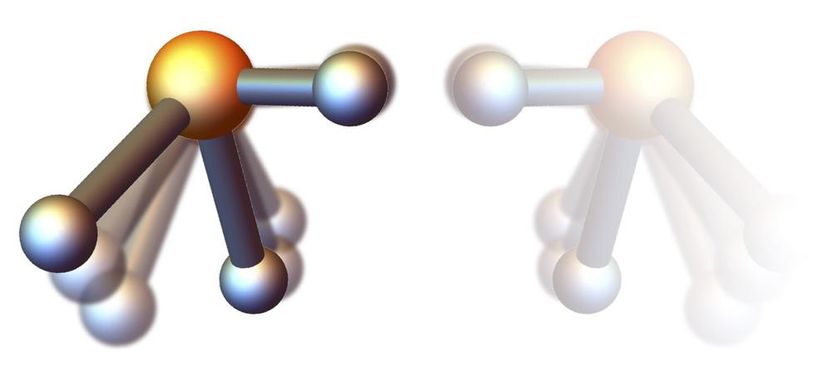

Due to the rapid rotation, the phosphine molecule loses its symmetry: The bond between phosphorus and hydrogen along the axis of rotation is shorter than the other two such bonds. Depending on the direction of rotation, two mirror-inverted versions of the molecule are formed.

DESY, Andrey Yachmenev

Like your hands, many molecules in nature exist in two versions that are mirror images of each other. “For unknown reasons, life as we know it on Earth almost exclusively prefers left-handed proteins, while the genome is organised as the famous right-handed double helix,” explains Andrey Yachmenev, who lead this theoretical work in Küpper's group at the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL). “For more than a century, researchers are unravelling the secrets of this handedness in nature, which does not only affect the living world: mirror versions of certain molecules alter chemical reactions and change the behaviour of materials.” For instance, the right-handed version of caravone (C10H14O) gives caraway its distinctive taste, while the left-handed version is a key factor for the taste of spearmint.

Handedness, or chirality, only occurs naturally in some types of molecules. “However, it can be artificially induced in so-called symmetric-top molecules,” says co-author Alec Owens from the Center for Ultrafast Imaging (CUI). “If these molecules are stirred fast enough, they lose their symmetry and form two mirror forms, depending on their sense of rotation. So far, very little is known about this phenomenon of rotationally-induced chirality, because hardly any schemes for its generation exist that can be followed experimentally.”

Küpper's team has now computationally devised a way to achieve this rotationally-induced chirality with realistic parameters in the lab. It uses corkscrew-shaped laser pulses known as optical centrifuges. For the example of phosphine (PH3) their quantum-mechanical calculations show that at rotation rates of trillions of times per second the phosphorus-hydrogen bond that the molecule rotates about becomes shorter than the other two of these bonds, and depending on the sense of rotation, two chiral forms of phosphine emerge. “Using a strong static electric field, the left-handed or right-handed version of the spinning phosphine can be selected,” explains Yachmenev. “To still achieve the ultra-fast unidirectional rotation, the corkscrew-laser needs to be fine-tuned, but to realistic parameters.”

This scheme promises a completely new path through the looking-glass into the mirror world, as it would in principle also work with other, heavier molecules. In fact, these would actually require weaker laser pulses and electric fields, but were just too complex to be solved in these first stages of the investigation. However, as phosphine is highly toxic, such heavier and also slower molecules would probably be preferred for experiments.

The proposed method could deliver tailor-made mirror molecules, and the investigation of their interactions with the environment, for instance with polarized light, should help to further penetrate the mysteries of handedness in nature and explore its possible utilization, expects Küpper, who is also a professor of physics and of chemistry at Universität Hamburg: “Faciliating a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of handedness this way could also contribute to the development of chirality-based tailor-made molecules and materials, novel states of matter, and the potential utilization of rotationally-induced chirality in novel metamaterials or optical devices.”