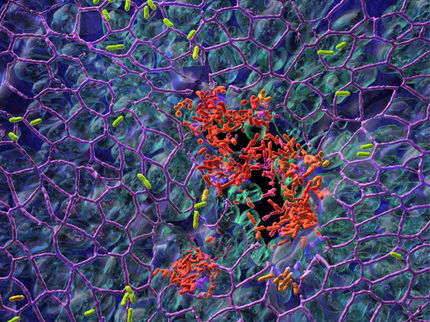

Cellular memory outwits pathogens

Study proves effectiveness of sequential antibiotic treatment against the pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa

The World Health Organization (WHO) warns that seemingly harmless bacterial infections could develop into one of the leading causes of death in the next few years, particularly in the industrialised countries. This dramatic threat arose because, in many cases, the antibiotics that have been prescribed for decades as a standard treatment have become ineffective due to increasing resistance, and this trend continues to gather pace. The root of the problem is the germs’ rapid evolutionary adaptation to the drugs used to combat them. The consequence is that even new antibiotics can become ineffective within a short period of time. Researchers around the world are therefore pursuing an alternative approach to the worsening antibiotics crisis, in order to regain the upper hand. They are trying to prolong the effectiveness of currently available active substances, through the application of evolutionary biological principles. A research team from the Kiel Evolution Center (KEC) at Kiel University (CAU) has teamed up with colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Plön and Uppsala University in Sweden to reveal a previously-unknown principle, which enables a completely new and at the same time highly sustainable form of treatment.

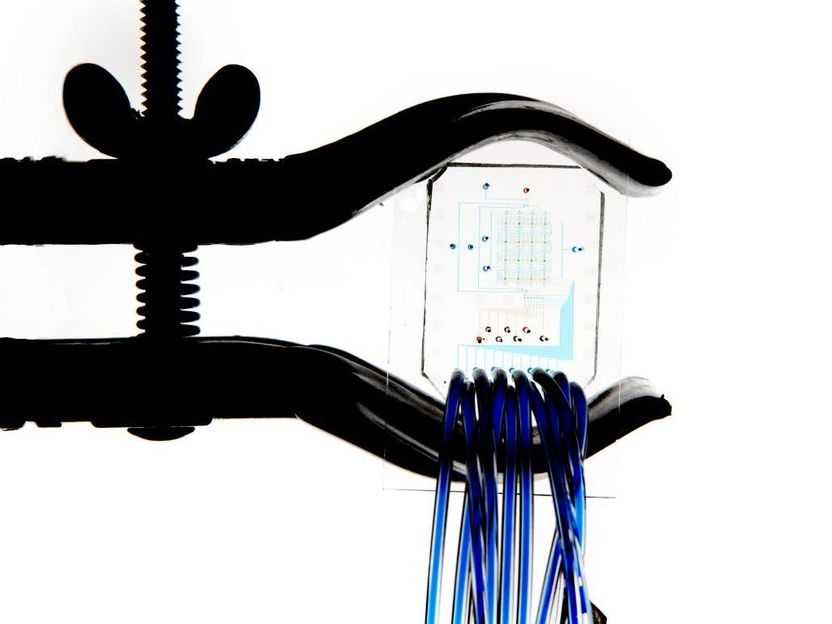

A short pre-treatment with penicillin increases the effectiveness of a subsequently applied aminoglycoside. Here we see a dilution series of a bacterial sample after the end of treatment, either without (3 columns on the left) or with pre-treatment (3 columns on the right).

© Christian Urban, Uni Kiel

The treatment process investigated makes use of a simple principle: short-term application of a particular antibiotic is followed by another antibiotic with a different mechanism of action. Using the example of the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which according to the WHO is one of the most critical threats of a multidrug resistant bacterium, the Kiel researchers tested the temporal alternation of antibiotics with different mechanisms of action. To do so, they examined around 200 bacterial populations in an evolution experiment over a total of 500 generations, and observed the effects of different antibiotics and various sequential treatment protocols. They discovered that the most effective sequential protocol started with a penicillin-like substance followed by a so-called aminoglycoside, especially if changes happen in short intervals.

"A short initial treatment makes the germs vulnerable, because it enables easier penetration of the bacterial cells by another drug. The second antibiotic basically finishes the job, and properly kills the remaining bacteria," explained Professor Hinrich Schulenburg, head of the Evolutionary Ecology and Genetics research group at the CAU, and KEC spokesperson. This effect is entirely dependent on the sequence of the alternating antibiotics. The sensitizing drug must be applied first, since it apparently modifies the structure of the bacterial cell walls, and thereby opens the door for the second antibiotic. In addition, the speed and the pattern of the sequence are decisive: "If we alternate the two drugs faster than in normal antibiotic treatment, and at random intervals, the then resistance evolution is inhibited most effectively," continued Schulenburg.

The reason for the success of the sequential treatment is the so-called cellular memory of the bacterial pathogens. The first antibiotic changes the cellular properties of the germs over multiple generations, to such an extent that the second antibiotic functions even better - despite being administered later. "It’s almost like the first antibiotic opens a door, which provides easier entry for the second antibiotic," explained Dr Roderich Römhild, research associate in the Evolutionary Ecology and Genetics research group, and first author of the publication. "This approach is particularly promising from an evolutionary point of view, since the pathogens are now forced to evolve a defence against opening the door - and thus against the cellular memory effect - instead of direct resistance to the antibiotic," said Römhild. In the experiment, a significant reduction in resistance was indeed confirmed.

Most surprisingly, around 30 years ago, exactly the same treatment protocol as the one proposed now was by coincidence tested on patients - with impressive results: in almost all cases, pathogen abundance was significantly reduced following the sequential antibiotic treatment; in half of the cases, the pathogens could no longer be detected, and the sequential protocol was clearly more effective than the standard treatment. However, the method never became part of medical practice, most likely because of the lack of an explanation for treatment success. "We are convinced that with our new results on the cellular memory effect, we have now found the missing explanation," emphasised Schulenburg. "The new work provides yet another example of how, with the help of evolutionary concepts and methods, we can obtain new ideas for sustainable treatment approaches," summarised the KEC spokesperson.