A new kind of vaccine based on spider silk

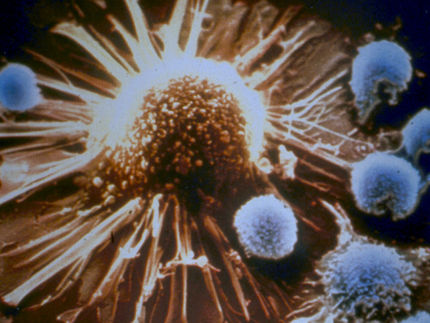

To fight cancer, researchers increasingly use vaccines that stimulate the immune system to identify and destroy tumour cells. However, the desired immune response is is not always guaranteed. In order to strengthen the efficacy of vaccines on the immune system - and in particular on T lymphocytes, specialized in the detection of cancer cells - researchers from the universities of Geneva (UNIGE), Freiburg (UNIFR), Munich, and Bayreuth, in collaboration with the German company AMSilk, have developed spider silk microcapsules capable of delivering the vaccine directly to the heart of immune cells. This process could also be applied to preventive vaccines to protect against infectious diseases, and constitutes an important step towards vaccines that are stable, easy to use, and resistant to the most extreme storage conditions.

Our immune system is largely based on two types of cells: B lymphocytes, which produce the antibodies needed to defend against various infections, and T lymphocytes. In the case of cancer and certain infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, T lymphocytes need to be stimulated. However, their activation mechanism is more complex than that of B lymphocytes: to trigger a response, it is necessary to use a peptide, a small piece of protein which, if injected alone, is rapidly degraded by the body even before reaching its target.

"To develop immunotherapeutic drugs effective against cancer, it is essential to generate a significant response of T lymphocytes,» says Professor Carole Bourquin, a specialist in antitumor immunotherapies at the faculties of medicine and science of the UNIGE, who directed this work. "As the current vaccines have only limited action on T-cells, it is crucial to develop other vaccination procedures to overcome this issue."

A virtually indestructible capsule

Scientists used synthetic spider silk biopolymers--a lightweight, biocompatible, non-toxic material that is highly resistant to degradation from light and heat. "We recreated this special silk in the lab to insert a peptide with vaccine properties,» explains Thomas Scheibel, a world specialist of spider silk from the University of Bayreuth who participated in the study. "The resulting protein chains are then salted out to form injectable microparticles."

Silk microparticles form a transport capsule that protects the vaccine peptide from rapid degradation in the body, and delivers the peptide to the center of the lymph node cells, thereby considerably increasing T lymphocyte immune responses. "Our study has proved the validity of our technique", reveals Carole Bourquin. "We have demonstrated the effectiveness of a new vaccination strategy that is extremely stable, easy to manufacture and easily customizable."

Towards a new vaccine model

The synthetic silk biopolymer particles demonstrate a high resistance to heat, withstanding over 100°C for several hours without damage. In theory, this process would make it possible to develop vaccines that do not require adjuvants and cold chains. An undeniable advantage, especially in developing countries where one of the great difficulties is the preservation of vaccines. One of the limitations of this process, however, is the size of the microparticles: while the concept is in principle applicable to any peptide, which are all small enough to be incorporated into silk proteins, further research is needed to see if it is also possible to incorporate the larger antigens used in standard vaccines, especially against viral diseases.

When science imitates nature

"More and more, scientists are trying to imitate nature in what it does best", adds Scheibel. "This approach even has a name: bioinspiration, which is exactly what we have done here." The properties of spider silk make it a particularly interesting product: biocompatible, solid, thin, biodegradable, resistant to extreme conditions and even antibacterial, one can imagine multiple applications, including wound dressings or sutures.

Original publication

Matthias Lucke, Inès Mottas et al.; "Engineered hybrid spider silk particles as delivery system for peptide vaccines"; Biomaterials; 172 (2018) 105e115.

Sushma Kumari, Hendrik Bargel et al.; "Recombinant Spider Silk Hydrogels for Sustained Release of Biologicals"; ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng; 2018, 4, 1750−1759.