How the food we eat affects biochemical signals in the gut

For years, researchers have studied how the body's microbiome impacts virtually every aspect of human health ranging from the immune system to mental wellness. Now, a recent study led by a multi-institutional research team, including the University of Maryland, several institutions in South Korea, and Purdue University, sheds new light on how the food we eat can affect the biochemical signaling processes in the gut microbiome.

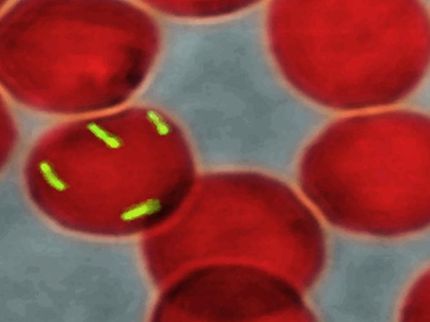

Food, symbolic picture

karriezhu; pixabay.com; CC0

The study is one of the first to link what we eat - and the generation of glucose - to a bacterial signaling process known as "quorum sensing." This process involves the synthesis of small signaling molecules, called autoinducers (AI), which are secreted by individual bacteria but serve to coordinate their responses. Once the AI level reaches a threshold - signaling a "quorum" of cells - the AI signals are transported intracellularly, where they activate gene expression and enable coordinated phenotypic responses.

This latest study identifies new linkages between quorum sensing activity and sugar metabolism in the gut, using AI-2, an autoinducer secreted by a wide variety of species of bacteria, said William E. Bentley, UMD Fischell Department of Bioengineering (BIOE) and Institute for Biosciences and Biotechnology Research (IBBR) Professor. Bentley, who also directs the UMD Robert E. Fischell Institute for Biomedical Devices, is a corresponding author of the paper, along with Kyoung-Seok Ryu (Korea Basic Science Institute) and Herman O. Sintim (Purdue University).

Bacteria use what is known as the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) for the uptake of sugars, including glucose and fructose. In E. coli, specifically, the phosphocarrier protein known as HPr plays a vital role in carrying out sugar transport.

AI-2 signaling relies on an enzyme known as LsrK for its phosphorylation - a process whereby enzymes are activated to regulate protein function within a cell. Often, biological signaling processes utilize what is known as a phosphorelay mechanism to alter behavior.

The interdisciplinary and trans-Pacific research team discovered that LsrK binds to HPr, which indicates that the quorum-sensing cell-cell communication is very much influenced by the glucose level.

"HPr had already been known to regulate glucose utilization, so this part of the equation was known," Sintim said. "But, we've now added that this also regulates quorum sensing."

Put simply, the group's findings suggest that the food we eat - and the resulting glucose level of the gastrointestinal tract - can affect the types of signals the microbiome encounters and also sends to other parts of the body.

"Our group has been working together for several years, and a long-term goal of ours is to elucidate the molecular communication pathways that govern physiological processes and link bacteria with human cells," Bentley said. "In biology, information transfer - and the way organisms function - depends entirely on 'communicating' molecules that move information back and forth among cells and tissues. The 'talk' between bacteria and human cells is complex, but vitally important. Studies such as these will form the basis for new antimicrobial therapies, and could even shape diet plans and exercise regimens to improve human health."

Original publication

Ha, Jung-Hye and Hauk, Pricila and Cho, Kun and Eo, Yumi and Ma, Xiaochu and Stephens, Kristina and Cha, Soyoung and Jeong, Migyeong and Suh, Jeong-Yong and Sintim, Herman O. and Bentley, William E. and Ryu, Kyoung-Seok; "Evidence of link between quorum sensing and sugar metabolism in Escherichia coli revealed via cocrystal structures of LsrK and HPr"; Science Advances; 2018