Cells change tension to make tissue barriers easier to get through

New mechanism by which signaling molecule can act in fruitflies

Advertisement

Fly cells squeeze through tissue barriers in the body better when these barriers are made less stiff. This is the result of a study by Daria Siekhaus, Professor at the Institute of Science and Technology (IST Austria) and her team, including first author and postdoc Aparna Ratheesh, which was published today in the journal Developmental Cell. This mechanism was previously unknown.

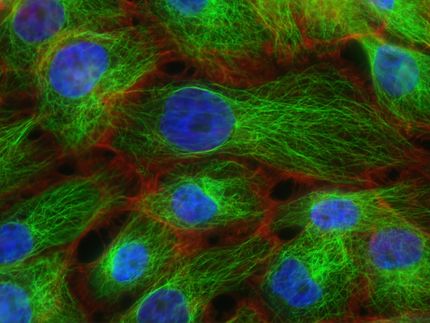

Like tiny building blocks, billions of cells form our bodies. But unlike building blocks, some cells are able to move around the body. This is important during development, but also when the immune system fights infections. The most notorious cell movement occurs during metastasis, when cancer cells spread from a primary tumor. To move around the body, some cell need to be able to get from one tissue into another – for example, when immune cell needs to get out of the blood vessel and into damaged or inflamed tissue. But some tissue barriers are made of cells that sit closely together, like a tight wall, making it hard for migrating cells to get through. In their study, Daria Siekhaus and her team report that in the fly, a type of immune cell called a macrophage has an easier time squeezing through when a signal is sent to change the tension of the cells within the wall. “We have found a new mechanism by which the movement of cells through tissue barriers is made easier ”, explains Daria Siekhaus.

New distinct mechanism

The researchers studied the movement of macrophages in the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster. Macrophages, which play an important role in development, and in responding to wounds, infections, or other threats to the organism, migrate through the developing fruitfly embryo. Along their way, they need to get through a tissue called the germband. The mechanism they use to achieve this, however, was not known until now. The researchers found that migrating macrophages stall when they reach this barrier. They spend time trying to push their way in, a task that is made easier by a signal sent to the cells of the barrier that reduces their tension. This change in tension makes the barrier cells less stiff and more deformable, allowing macrophages to more easily squeeze between them.

Interestingly, Daria Siekhaus and her team found that this signal which tells the tissue barrier to be softer is Eiger, the Drosophila form of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a signaling molecule that is important for inflammatory signaling in vertebrates. Binding to its receptor Grindelwald, Eiger changes the localization of another protein, Patj, that controls the activity of Myosin, a motor protein essential for generating and maintaining cellular tension.

Cells as rubber bands

To prove their hypothesis, the researchers used a technique that has been developed previously, called laser ablation, to cut through the edge of the cells under a microscope. Similar to when a rubber band snaps and the ends move away from one another the cut edges of the cell separate. The greater the tension in a rubber band as it snaps, the faster the ends spring apart. The same holds true for cells, and by measuring the speed of separation, the researchers can calculate under how much tension the cell was in the first place. In mutant embryos, in which no Eiger molecule signals to the barrier cells, Myosin activity in the cells is higher and the cells snap apart quicker than in wild-type cells, i.e. they are under more tension.

“When tension in surrounding cells is higher, immune cell migration across the barrier is reduced. We have shown the physical effects of these molecular changes, and have defined a new pathway by which a TNF can act”, Daria Siekhaus explains. Aparna Ratheesh, first author of the study, is excited by the active process of invasion they identified: “Macrophages squeeze between cells. In doing so, they force their way into a place and shape the surrounding tissue. This pushing has to be controlled and directed, and leads to an active invasion.” As TNF signaling molecules also play an important role in vertebrates, their results potentially have importance beyond the fruitfly, Siekhaus says: “We have some data that TNF plays a role in the migration of immune cells during the development of vertebrates. So our results may also be important in the vertebrate context.”

Original publication

Aparna Ratheesh, Julia Biebl, Jana Vesela, Michael Smutny, Ekaterina Papusheva, S.F. Gabriel Krens, Walter Kaufmann, Attila Gyoergy, Alessandra Maria Casano, Daria E. Siekhaus; "Drosophila TNF Modulates Tissue Tension in the Embryo to Facilitate Macrophage Invasive Migration"; Developmental Cell; 2018