Ebola virus gene stolen and preserved by myotis bats

Advertisement

A gene from the deadly Ebola virus that allows the virus to escape from the human immune system has been identified in the genome of a group of bats that is found worldwide, including North America. The gene appears to have been stolen from the virus by the bats and adapted to regulate their own immune response, according to a recent study led by Georgia State University.

The research team's work focuses on Ebola virus and the related Marburg virus, which are single-stranded RNA viruses that belong to the filovirus family and are well-known for being deadly pathogens.

"It's quite striking that several years ago genes were found in some mammalian species that look like Ebola virus genes," said Dr. Christopher Basler, a professor in the Institute for Biomedical Sciences at Georgia State, director of the university's Center for Microbial Pathogenesis and a Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Microbial Pathogenesis. "The most interesting and striking of these is an Ebola virus gene that produces a protein called VP35.

"If you look in a certain genus of bats, the Myotis genus, they all contain what appears to be a copy of VP35 gene from Ebola virus. It's not identical to what you find in the virus, but it's clearly quite similar. All of the bats in this genus have this gene. These bats are scattered all over the globe. The gene has been there about 18 million years. If it's been preserved all this time, it must be there for a reason. We wanted to ask, what is the function of this gene in the bats?"

In the Ebola virus, the VP35 gene blocks the immune response of humans or animals being infected by the virus in order to cause the deadly disease. Based on the researchers' previous studies, if the virus doesn't make a functional copy of this protein, the Ebola virus can't cause disease.

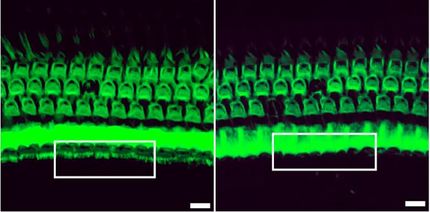

In this study, the researchers studied the VP35 gene in cells derived from Myotis bats, also known as mouse-eared bats, to understand whether this gene has a similar function in these mammals. The findings are published in the journal Cell Reports.

"We found that the version in the bats is attenuated [weakened] in its ability to inhibit the immune response. So, the Ebola VP35 is very potent, and this one is very attenuated," said Dr. Megan Edwards, first author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher in the Institute for Biomedical Sciences at Georgia State. "And it doesn't have several of the other functions that are attributed to Ebola VP35. However, the structure of the protein is strikingly similar, nearly identical, to the Ebola VP35. So, it hasn't conserved the potent function, but it has evolutionarily conserved the structure."

"We think it [the gene] has evolved to have maybe a related, but somewhat different function than what it does in the virus," Basler said. "In Myotis bats, the gene is still able to block immune responses at some level, but it does it less efficiently than the virus. The goal of this gene in the virus is to completely shut off the immune system, so that allows it to grow unimpeded. But the host wants to keep its immune system intact, so one idea is maybe this gene serves to regulate the immune system. However, it's also possible that it does other things that we don't yet understand."

In addition to Myotis bats, the VP35 gene has been found in other mammals: the wallaby (members of the kangaroo family), the tarsier (small primates found on some islands of Southeast Asia) and rodents. The wallaby and tarsier have the most intact genetic sequence. (Ebola is an RNA virus and the copy of this gene in mammals is a DNA copy, so the gene has been reverse transcribed, which is not a normal part of the viral life cycle.)

"Similar things seem to have happened at other times in other mammals," Basler said. "There seems to be something that some animals like about this sequence and have adapted for their own use."

Most people normally think of Ebola virus as a very scary and deadly pathogen. The fact that Ebola virus can donate a gene that proved useful to an animal supports the idea that some animals have very different relationships with Ebola virus than do humans, Basler explained.

Original publication

Megan R. Edwards, Hejun Liu, Reed S. Shabman, Garrett M. Ginell, Priya Luthra, Parmeshwaran Ramanan, Lisa J. Keefe, Bernd Köllner, Gaya K. Amarasinghe, Derek J. Taylor, Daisy W. Leung, Christopher F. Basler; "Conservation of Structure and Immune Antagonist Functions of Filoviral VP35 Homologs Present in Microbat Genomes"; Cell Reports; 2018