How pathogenic bacteria prepare a sticky adhesion protein

Advertisement

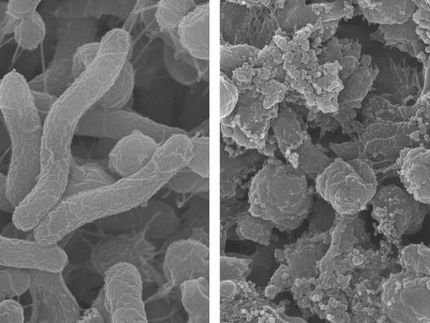

Researchers at Harvard Medical School, the University of California, San Francisco, and the University of Georgia have described how the protein that allows strep and staph bacteria to stick to human cells is prepared and packaged. The research could facilitate the development of new antibiotics.

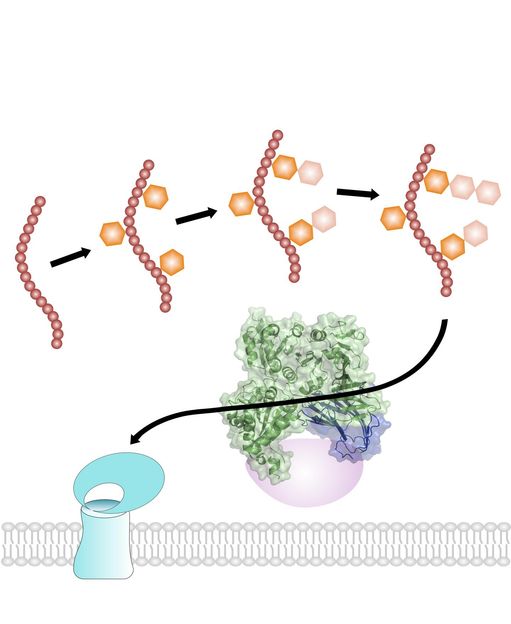

Pathogenic gram-positive bacteria, such as S. gordonii, export a serine-rich adhesin to facilitate their attachment to host cells. Adhesin uses a dedicated secretion pathway, with several steps occurring in the cytosol before its translocation across the membrane. The adhesin GspB (shown in red) is first modified by N-acetylglucosamine (orange hexagon) and glucose (wheat hexagon) in a strictly sequential order. It is then targeted to the membrane by a complex of three accessory secretion proteins (Asp 1-3; shown in green, blue, and pink), two of which resemble carbohydrate-binding proteins (crystals structures are shown ribbon diagrams imbedded in space-filling presentation). Finally, GspB adhesin is moved through the membrane by a dedicated ATPase (SecA2) and membrane channel (SecY2) (both shown in cyan).

Yu Chen, Harvard Medical School

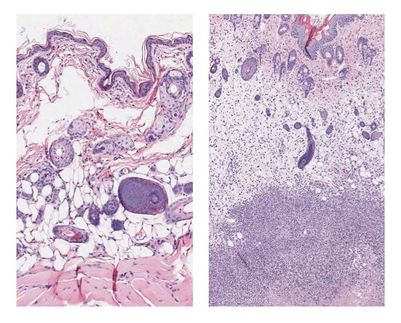

All bacteria have a standard secretion system that allows them to export different types of proteins outside of their cells. An important class of extracellular molecules produced by pathogenic bacteria are adhesins, proteins that enable bacteria to adhere to host cells. For unknown reasons, the SRR (serine-rich-repeat) adhesins of Staphylococcus and Streptococcus bacteria - pathogens that can be involved in serious infections such as bacterial meningitis, bacterial pneumonia and pericarditis - are transported through a secretion pathway that is similar to the standard system, but dedicated solely to adhesin.

It would be as if a warehouse that processes many types of goods were to have a separate set of doors and forklifts for just one of its wares. Tom Rapoport, a professor at Harvard Medical School who oversaw the new study, wanted to understand what exactly these dedicated molecular supply chains were doing.

"I was intrigued by the fact that there is a second secretion system in some bacteria that is separate from the canonical secretion system and is just dedicated to the secretion of one protein," Rapoport said. "There is a whole machinery, and it's only doing one thing."

Yu Chen, at the time a postdoctoral research associate in Rapoport's lab, led the investigation. She found that, in order to be transported, the adhesin protein needed to be modified with specific sugars by three enzymes acting in a specific sequence. These sugar modifications stabilize the protein and enhance its stickiness to target cells. Furthermore, the experiments showed that two proteins in the adhesin-specific pathway, whose function had previously been mysterious, seemed to be able to bind to these sugars, presumably enabling them to carry the adhesin to the cell membrane where adhesin's dedicated exit channel is located.

The complexity of the adhesin transport system necessitated collaboration with research teams at UCSF, Harvard Medical School, and the University of Georgia. Members of Paul Sullam's lab at UCSF provided the clinical perspective, members of Maofu Liao's lab at Harvard characterized the targeting complex by electron microscopy, and members of Parastoo Azadi's lab at Georgia analyzed the sugar modifications.

"It's a complicated system because it involves protein modification, chaperone activity and membrane targeting, so we encountered a lot of challenges," Chen said. "This (study) is a great example of how collaboration across labs in the scientific community advances human knowledge."

The reason that these bacteria use this separate export pathway for adhesins remains elusive. But because this pathway is unique to strep and staph bacteria, the new understanding of its components could help researchers develop highly targeted antibiotics to treat infections caused by these bacteria in the future.

"You could imagine that you could develop novel antibiotics that could target this pathway," Rapoport said. "(They) would be very specific for pathogenic bacteria."

Original publication

Yu Chen, Barbara A. Bensing, Ravin Seepersaud, Wei Mi, Maofu Liao, Philip D. Jeffrey, Asif Shajahan, Roberto N. Sonon, Parastoo Azadi, Paul M. Sullam, and Tom A. Rapoport; "Unraveling the sequence of cytosolic reactions in the export of GspB adhesin from Streptococcus gordonii"; J. Biol. Chem.; 2018