Progress in pursuit of sickle cell cure

Scientists have successfully used gene editing to repair 20 to 40 percent of stem and progenitor cells taken from the peripheral blood of patients with sickle cell disease, according to Rice University bioengineer Gang Bao.

Bao, in collaboration with Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children's Hospital and Stanford University, is working to find a cure for the hereditary disease. A single DNA mutation causes the body to make sticky, crescent-shaped red blood cells that contain abnormal hemoglobin and can block blood flow in limbs and organs.

In his talk at the annual American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in Austin today, Bao revealed results from a series of tests to see whether CRISPR/Cas9-based editing can fix the mutation. His presentation was part of a scientific session titled "Gene Editing and Human Identity: Promising Advances and Ethical Challenges."

"Sickle cell disease is caused by a single mutation in the beta-globin gene (in the stem cell's DNA)," he said. "The idea is to correct that particular mutation, and then stem cells that have the correction would differentiate into normal blood cells, including red blood cells. Those will then be healthy blood cells."

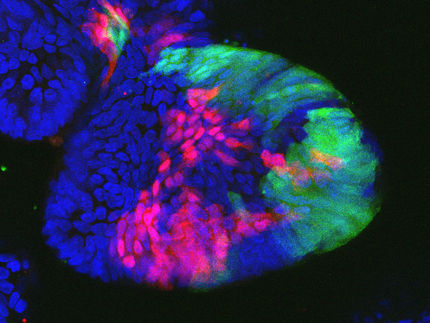

Bao's lab collaborated with Vivien Sheehan, an assistant professor of pediatrics and hematology at Baylor and a member of the sickle cell program at Texas Children's, to collect stem and progenitor cells (CD34-positive cells) from patients with the disease. These were then edited in the Bao lab with CRISPR/Cas9 together with a custom template, a piece of DNA designed to correct the mutation.

The gene-edited cells were injected into the bone marrow of immunodeficient mice and tested after 19 weeks to see how many retained the edit. "The rate of repair remained stable, which is great," Bao said. This engraftment study was carried out in the lab of Matt Porteus, an associate professor of pediatrics at Stanford.

Another major finding of the study is that the CRISPR/Cas9 system could introduce large alterations to the genes in patients' cells, in addition to small mutations or deletions. These off-target effects could cause a disease.

The findings, part of an upcoming paper, are a step toward treating sickle cell disease. Obstacles in the way of a cure include optimizing the CRISPR/Cas9 system to eliminate off-target effects, as well as finding a way to further increase the amount of gene-corrected stem cells.

Bao pointed out that researchers still don't know whether repairing as much as 40 percent of the cells is enough to cure a patient. "We'd like to say, 'Yes,'" he said, "but we don't really know yet. That's something we hope to learn from an eventual clinical trial."

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

New analgesic could replace opioids over the long term - Researchers find a natural active substance that could replace opioids in the long term and alleviate the opioid crisis

Texas A&M team finds neuron responsible for alcoholism