New antifungal provides hope in fight against superbugs

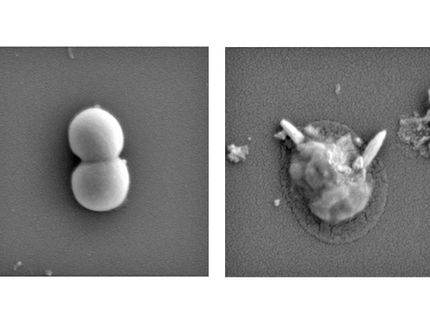

Microscopic yeast have been wreaking havoc in hospitals around the world--creeping into catheters, ventilator tubes, and IV lines--and causing deadly invasive infection. One culprit species, Candida auris, is resistant to many antifungals, meaning once a person is infected, there are limited treatment options. But in a recent study, researchers confirmed a new drug compound kills drug-resistant C. auris, both in the laboratory and in a mouse model that mimics human infection.

The drug works through a novel mechanism. Unlike other antifungals that poke holes in yeast cell membranes or inhibit sterol synthesis, the new drug blocks how necessary proteins attach to the yeast cell wall. This means C. auris yeast can't grow properly and have a harder time forming drug-resistant communities that are a stubborn source of hospital outbreaks. The drug's target--a yeast enzyme called Gwt1--is also highly conserved across fungal species, suggesting the new drug could treat a range of infections.

The drug is first in a new class of antifungals, which could help stave off drug resistance. Even the most troublesome strains are unlikely to have developed workarounds for its mechanism of action, says study lead Mahmoud A. Ghannoum, PhD, professor of dermatology at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and director of the Center for Medical Mycology at Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

In the new study, Ghannom's team tested the drug against 16 different C. auris strains, collected from infected patients in Germany, Japan, South Korea, and India. When they exposed the isolates to the new drug, they found it more potent than nine other currently available antifungals. According to the authors, the concentration of study drug needed to kill C. auris growing in laboratory dishes was "eight-fold lower than the next most active drug, anidulafungin, and more than 30-fold lower than all other compounds tested."

The researchers also developed a new mouse model of invasive C. auris infection for the study. Said Ghannoum, "To help the discovery of effective drugs it will be necessary to have an animal model that mimics this infection. Our work helps this process in two ways: first we developed the needed animal model that mimics the infection caused by this devastating yeast, and second, we used the developed model to show the drug is effective in treating this infection."

They studied immunocompromised mice infected with C. auris via their tail vein--similar to very sick humans in hospitals who experience bloodstream infections. Compared to mice treated with anidulafungin, infected mice treated with the new drug had significant reductions in kidney, lung, and brain fungal burden two days post-treatment. The results suggest the new drug could help treat even the most invasive infections.

According to Ghannoum, the most exciting element of the study is that it brings a promising antifungal one step closer to patients. It helps lay the foundation for phase 1 clinical trials that study low levels of the drug in healthy adults and test for any potential safety concerns. There is an urgent need for such studies, as C. auris infection has become a serious threat to healthcare facilities worldwide--and drug-resistance is rising.

"Limited treatment options calls for the development of new drugs that are effective against this devastating infection," Ghannoum said. "We hope that we contributed in some way towards the development of new drugs."

Original publication

Most read news

Original publication

Christopher L. Hager, Emily L. Larkin, Lisa Long, Fatima Z. Abidi, Karen J. Shaw, and Mahmoud A. Ghannoum; "In vitro and in vivo Evaluation of the Antifungal Activity of APX001A/APX001 Against Candida auris"; Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.; 2018

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Capricorn Scientific and ExcellGene Form Strategic Partnership to Support Biotech Industries - This customer-oriented approach is dedicated to accelerating the biotech journey from R&D up to clinical production

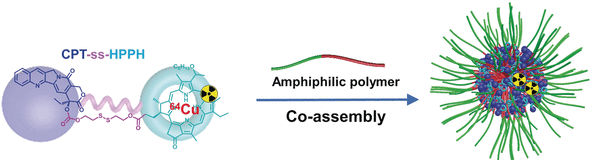

Combination Pack Battles Cancer - Nanoparticles with multifunctional drug precursor for synergistic tumor therapy

PharmaKure announces collaboration with Sheffield Hallam University to understand mechanisms of Alzheimer’s Diseases - New collaboration will enhance ability to identify those more at risk of developing brain diseases to enable earlier interventions

From plants to plastics - Biomass transferred into valuable chemicals

Discover the world of biopharmaceutical manufacturing - bionity.com presents new topic world for biopharmaceutical production

UC San Diego Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Janssen R&D collaborate to treat Chagas disease - Team will seek new therapeutic targets and treatments for this neglected tropical disease