Bacteria acquire resistance from competitors

Advertisement

bacteria not only develop resistance to antibiotics, they also can pick it up from their rivals. In a recent publication in "Cell Reports", Researchers from the Biozentrum of the University of Basel have demonstrated that some bacteria inject a toxic cocktail into their competitors causing cell lysis and death. Then, by integrating the released genetic material, which may also carry drug resistance genes, the predator cell can acquire antibiotic resistance.

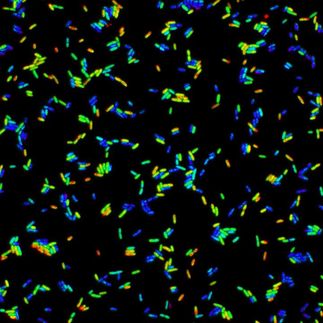

Bacterial competition at the microscale: The T6SS (green, magenta) mediated killing and lysis of competing bacteria can lead to DNA release (cyan) and subsequent gene transfer.

Biozentrum of the University of Basel

The frequent and sometimes careless use of antibiotics leads to an increasingly rapid spread of resistance. Hospitals are a particular hot spot for this. Patients not only introduce a wide variety of pathogens, which may already be resistant but also, due to the use of antibiotics to combat infections, hospitals may be a place where anti-microbial resistance can develop and be transferred from pathogen to pathogen. One of these typical hospital germs is the bacterium Acinetobacter baumannii. It is also known as the "Iraq bug" because multidrug-resistant bacteria of this species caused severe wound infections in American soldiers during the Iraq war.

Multidrug-resistant bacteria due to gene exchange

The emergence and spread of multidrug resistance could be attributed, among other things, to the special skills of certain bacteria: Firstly, they combat their competitors by injecting them with a cocktail of toxic proteins, so-called effectors, using the type VI secretion system (T6SS), a poison syringe. And secondly, they are able to uptake and reuse the released genetic material. In the model organism Acinetobacter baylyi, a close relative of the Iraq bug, Prof. Marek Basler's team at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel, has now identified five differently acting effectors. "Some of these toxic proteins kill the bacterial competition very effectively, but do not destroy the cells," explains Basler. "Others severely damage the cell envelope, which leads to lysis of the attacked bacterium and hence the release of its genetic material."

The predator bacteria take up the released DNA fragments. If these fragments carry certain drug resistance genes, the specific resistance can be conferred upon the new owner. As a result, the antibiotic is no longer effective and the bacterium can reproduce largely undisturbed.

Pathogens with such abilities are a major problem in hospitals, as through contact with other resistant bacteria they may accumulate resistance to many antibiotics - the bacteria become multidrug-resistant. In the worst case, antibiotic treatments are no longer effective, thus nosocomial infections with multidrug-resistant pathogens become a deadly threat to patients.

Toxic proteins and antitoxins

"The T6SS, as well as a set of different effectors, can also be found in other pathogens such as those which cause pneumonia or cholera," says Basler. Interestingly, not all effectors are sufficient to kill the target cell, as many bacteria have developed or acquired antitoxins - so-called immunity proteins. "We have also been able to identify the corresponding immunity proteins of the five toxic effectors in the predator cells. For the bacteria it makes absolute sense to produce not only a single toxin, but a cocktail of various toxins with different effects," says Basler. “This increases the likelihood that the rivals can be successfully eliminated and in some cases also lysed to release their DNA.”

Conquest of new environmental niches

Antibiotics and anti-microbial resistance have existed for a long time. They developed through the coexistence of microorganisms and enabled bacteria to defend themselves against enemies or to eliminate competitors. This is one of the ways in which bacteria can conquer and colonize new environmental niches. With the use of antibiotics in medicine, however, the natural ability to develop resistance has become a problem. This faces researchers with the challenge of continually developing new antibiotics and slowing down the spread of drug resistance.