New Research Rejects 80-year Theory of ‘Primordial Soup’ as the Origin of Life

Earth’s Chemical Energy Powered Early Life through ‘the most revolutionary idea in biology since Darwin.’

For 80 years it has been accepted that early life began in a ‘primordial soup’ of organic molecules before evolving out of the oceans millions of years later. Today the ‘soup’ theory has been over turned in a pioneering paper in BioEssays which claims it was the Earth’s chemical energy, from hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, which kick-started early life.

“Textbooks have it that life arose from organic soup and that the first cells grew by fermenting these organics to generate energy in the form of ATP. We provide a new perspective on why that old and familiar view won't work at all,” said team leader Dr Nick lane from University College London. “We present the alternative that life arose from gases (H2, CO2, N2, and H2S) and that the energy for first life came from harnessing geochemical gradients created by mother Earth at a special kind of deep-sea hydrothermal vent – one that is riddled with tiny interconnected compartments or pores.”

The soup theory was proposed in 1929 when J.B.S Haldane published his influential essay on the origin of life in which he argued that UV radiation provided the energy to convert methane, ammonia and water into the first organic compounds in the oceans of the early earth. However critics of the soup theory point out that there is no sustained driving force to make anything react; and without an energy source, life as we know it can’t exist.

"Despite bioenergetic and thermodynamic failings the 80-year-old concept of primordial soup remains central to mainstream thinking on the origin of life," said senior author, William Martin, an evolutionary biologist from the Insitute of Botany III in Düsseldorf. "But soup has no capacity for producing the energy vital for life."

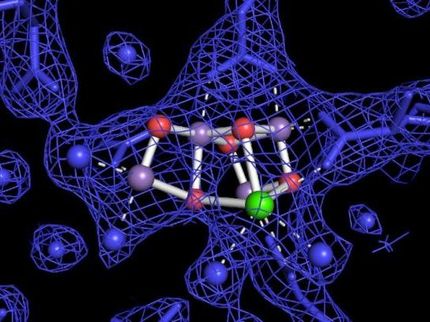

In rejecting the soup theory the team turned to the Earth's chemistry to identify the energy source which could power the first primitive predecessors of living organisms: geochemical gradients across a honeycomb of microscopic natural caverns at hydrothermal vents. These catalytic cells generated lipids, proteins and nucleotides giving rise to the first true cells.

The team focused on ideas pioneered by geochemist Michael J. Russell, on alkaline deep sea vents, which produce chemical gradients very similar to those used by almost all living organisms today - a gradient of protons over a membrane. Early organisms likely exploited these gradients through a process called chemiosmosis, in which the proton gradient is used to drive synthesis of the universal energy currency, ATP, or simpler equivalents. Later on cells evolved to generate their own proton gradient by way of electron transfer from a donor to an acceptor. The team argue that the first donor was hydrogen and the first acceptor was CO2.

“Modern living cells have inherited the same size of proton gradient, and, crucially, the same orientation – positive outside and negative inside – as the inorganic vesicles from which they arose” said co-author John Allen, a biochemist at Queen Mary, University of London.

“Thermodynamic constraints mean that chemiosmosis is strictly necessary for carbon and energy metabolism in all organisms that grow from simple chemical ingredients [autotrophy] today, and presumably the first free-living cells,” said Lane. “Here we consider how the earliest cells might have harnessed a geochemically created force and then learned to make their own.”

This was a vital transition, as chemiosmosis is the only mechanism by which organisms could escape from the vents. “The reason that all organisms are chemiosmotic today is simply that they inherited it from the very time and place that the first cells evolved – and they could not have evolved without it,” said Martin.

“Far from being too complex to have powered early life, it is nearly impossible to see how life could have begun without chemiosmosis”, concluded Lane. “It is time to cast off the shackles of fermentation in some primordial soup as ‘life without oxygen’ – an idea that dates back to a time before anybody in biology had any understanding of how ATP is made.”

Original publication: Nick Lane, John F. Allen and William Martin, ‘How did LUCA make a living? Chemiomosis in the origin of life,’ BioEssays, Wiley-Blackwell, February 2010.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Bunion

Tammar_Wallaby

Ergot

Atlas_(anatomy)

Ataxia

5 Leading Multinationals Announce R&D Projects for Ireland - Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Pfizer Inc., Genzyme Corporation, Xilinx Inc. Citigroup are investing a total of EUR 53.25 million

Can cell ageing be stopped? - Tiny switches in the cell systems can positively influence ageing

2,5-Dimethylfuran

Histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate

Experimental insecticide explodes mosquitoes, not honeybees

VAI researchers find long awaited key to creating drought resistant crops - Findings could help engineer hardier plants and have implications for stress disorders in humans