Chaperones for climate protection

The protein Rubisco locks up carbon dioxide

The World Climate Conference recently took place. Reports about carbon dioxide levels, rising temperatures and melting glaciers appear daily. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute (MPI) of biochemistry and the Gene Center of Ludwig Maximilians University Munich have now succeeded in rebuilding the enzyme Rubisco, the key protein in carbon dioxide fixation. "Rubisco is one of the most important proteins on the planet, yet despite this, it is also one of the most inefficient", says Manajit Hayer-Hartl, a group leader at the MPI of Biochemistry. The researchers are now working on modifying the artificially produced Rubisco so that it will convert carbon dioxide more efficiently than the original protein.

Rubisco binds carbon dioxide and facilitates the conversion to sugar and oxygen.

Max-Planck-Institut für Biochemie / Andreas Bracher

Photosynthesis is one of the most important biological processes. Plants metabolize carbon dioxide and water into oxygen and sugar in the presence of light. Without this process, life on earth as we know it would not be possible. The key protein in photosynthesis, Rubisco, is thus one of the most important proteins in nature. It bonds with carbon dioxide and starts its conversion into sugar and oxygen. "But this process is really inefficient", explains Manajit Hayer-Hartl. "Rubisco not only reacts with carbon dioxide but also quite often with oxygen." This did not cause any problems with the protein developed three billion years ago. Back then, there was no oxygen present in the atmosphere. However, as more and more oxygen accumulated, Rubisco could not adjust to this change.

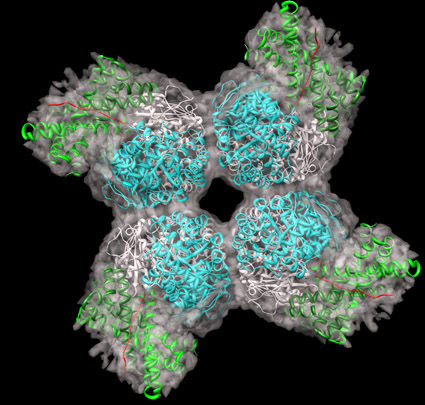

The protein Rubisco is a large complex consisting of 16 subunits. Up to now, its complex structure made it impossible to reconstruct Rubisco in the laboratory. To overcome this obstacle, scientists at the MPI of Biochemistry and at the Gene Center of the Ludwig Maximilians University Munich used the help of cellular chaperones. The French term chaperone describes a woman who accompanies a young lady to a date and takes care that the young gentleman will not approach her protégé improperly. The molecular chaperones within the cell work in a similar way: They ensure that only the correct parts of a newly synthesized protein will come together. As a result of this process, the protein acquires its correct three dimensional structure. "With 16 subunits like those of Rubisco, the risk is very high that the wrong parts of the protein clump together and form useless aggregates," says the biochemist. Only with its correct structure will Rubisco be able to fulfil its function in plants.

The MPI researchers showed that two different chaperone systems, called GroEL and RbcX, are necessary to produce a functional Rubisco complex. The next aim of the scientists is to genetically modify Rubisco so that it bonds with carbon dioxide more often and metabolizes oxygen less frequently. "Because the modified Rubisco is predicted to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere more effectively," says Manajit Hayer-Hartl, "it would enhance crop yields and could also be interesting for climate protection."

Original publication: C. Liu et al.; "Coupled chaperone action in folding and assembly of hexadecameric Rubisco"; Nature, January 14, 2010

Most read news

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.