Scientists reveal malaria parasites' tactics for outwitting our immune systems

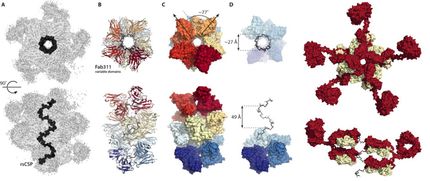

malaria parasites are able to disguise themselves to avoid the host's immune system, according to research funded by the Wellcome Trust and published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The malaria parasite infects healthy red blood cells, where it reproduces. The P. falciparum parasite generates a family of molecules, known as PfEMP1, that are inserted into the surface of the infected red blood cells. The cells become sticky and adhere to the walls of blood vessels in tissues such as the brain. This prevents the cells being flushed through the spleen, where the parasites would be destroyed by the body's immune system, but also restricts blood supply to vital organs.

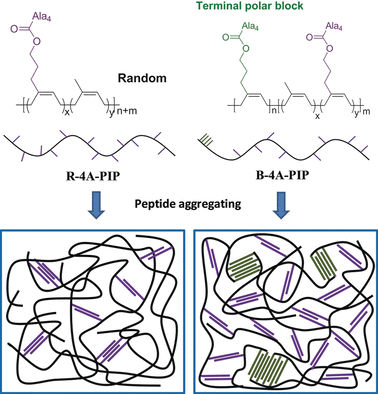

Each parasite has 'recipes' for around sixty different types of PfEMP1 molecule written into its genes. However, the exact recipes differ from parasite to parasite, so every new infection may carry a set of molecules that the immune system has not previously encountered. This has meant that in the past, researchers have ruled out the molecules as vaccine candidates. However there appear to be at least two main classes of PfEMP1 types within every parasite, suggesting different broad tactical approaches to infecting the host. The most efficient tactic or combination of tactics to use may depend on the host's immunity.

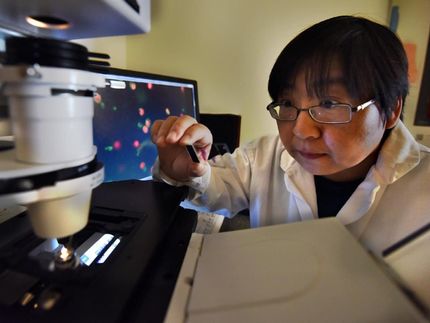

Now, Dr George Warimwe and colleagues from the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI)-Wellcome Trust Programme and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, have shown that the parasites adapt their molecules depending on which antibodies it encounters in the host's immune response. They have also found evidence to suggest that there may be a limit to the number of molecular types that are actually associated with severe disease.

"The malaria parasite is very complex, so our immune system mounts many different responses, some more effective than others and many not effective at all," explains Dr Peter Bull from the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Programme and the University of Oxford, who led the research. "We know that our bodies have great difficulty in completely clearing infections, which begs the question: how does the parasite manage to outwit our immune response? We have shown that, as children begin to develop antibodies to parasites, the malaria parasite changes its tactics to adapt to our defences."

The researchers at the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Programme studied malaria parasites in blood samples from 217 Kenyan children with malaria. They found that a group of genes coding for a particular class of PfEMP1 molecule called Cys-2 tended to be switched on when the children had a low immunity to the parasite; as immunity develops, the parasite switches on a different set of genes, effectively disguising it so that immune system cannot clear the infection

Dr Warimwe and colleagues also found an independent association between activity in Cys-2 genes and severe malaria in the children, suggesting that specific forms of the molecule may be more likely to trigger specific disease symptoms. This supports a previous study in Mali which suggested that the same class of PfEMP1 molecule was associated with cerebral malaria.

The findings could suggest a new approach to tackling malaria, in terms of both vaccine development and drug interventions, argues Dr Bull. "If there exists a limited class of severe disease-causing variants that naturally-exposed children learn to recognise readily, this opens up the possibility of designing a vaccine against severe malaria that mimics an adult's immune response, making the infections less dangerous. But this would still be an enormous task.

"Similarly, if we can establish what the particular class of molecules are doing, then we may be able to develop a drug to modify this function and relieve symptoms of severe disease."

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Antibodies

Antibodies are specialized molecules of our immune system that can specifically recognize and neutralize pathogens or foreign substances. Antibody research in biotech and pharma has recognized this natural defense potential and is working intensively to make it therapeutically useful. From monoclonal antibodies used against cancer or autoimmune diseases to antibody-drug conjugates that specifically transport drugs to disease cells - the possibilities are enormous

Topic world Antibodies

Antibodies are specialized molecules of our immune system that can specifically recognize and neutralize pathogens or foreign substances. Antibody research in biotech and pharma has recognized this natural defense potential and is working intensively to make it therapeutically useful. From monoclonal antibodies used against cancer or autoimmune diseases to antibody-drug conjugates that specifically transport drugs to disease cells - the possibilities are enormous