Researchers discover biological basis of 'bacterial immune system'

Advertisement

bacteria don't have easy lives. In addition to mammalian immune systems that besiege the bugs, they have natural enemies called bacteriophages, viruses that kill half the bacteria on Earth every two days. Still, bacteria and another class of microorganisms called archaea manage just fine, thank you, in part because they have a built-in defense system that helps protect them from many viruses and other invaders. A team of scientists led by researchers at the University of Georgia has now discovered how this bacterial defense system works, and it could lead to new classes of targeted antibiotics, new tools to study gene function in microorganisms and more stable bacterial cultures used by food and biotechnology industries to make products such as yogurt and cheese. The research was published in Cell .

"Understanding how bacteria defend themselves gives us important information that can be used to weaken bacteria that are harmful and strengthen bacteria that are helpful," said Michael Terns, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology in UGA's Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. "We also hope to exploit this knowledge to develop new tools to speed research on microorganisms."

Other authors on the Cell paper include Rebecca Terns, a senior research scientist in biochemistry and molecular biology at UGA; Caryn Hale, a graduate student in the Terns lab at UGA; Lance Wells, an assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and Georgia Cancer Coalition Scholar at UGA and his graduate student Peng Zhao; and research associate Sara Olson, assistant professor Michael Duff and associate professor Brenton Graveley of the University of Connecticut Health Center.

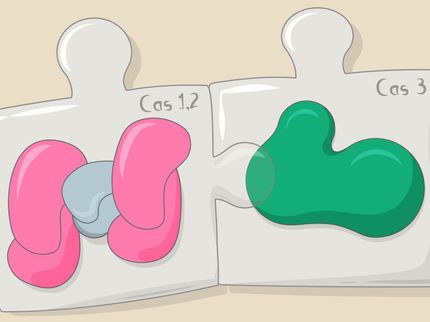

The system, whose mechanism of action was uncovered in the Terns lab (Michael and Rebecca Terns are a husband-wife team), involves a "dynamic duo" made up of a bacterial RNA that recognizes and physically attaches itself to a viral target molecule, and partner proteins that cut up the target, thereby "silencing" the would-be cell killer.

The invader surveillance component of the dynamic duo (an RNA with a viral recognition sequence) comes from sites in the genomes of bacteria and archaea, known technically as "clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats" or more familiarly called CRISPRs. CRISPR RNAs don't work alone in fighting invaders, though. Their partners in invader defense are Cas proteins that arise from a suite of genes called "CRISPR-associated" or Cas genes. Together, they form the "CRISPR-Cas system," and the new paper describes this dynamic duo and how they protect bacteria from viruses.

"You can look at one as a police dog that tracks down and latches onto an invader, and the other as a police officer that follows along and `silences' the offender," said Rebecca Terns. "It functions like our own immune system, constantly watching for and neutralizing intruders. But the surveillance is done by tiny CRISPR RNAs rather than antibodies."

What the team discovered was that a particular complex of CRISPR RNAs and a subset of the Cas proteins termed the RAMP module recognizes and destroys invader RNAs that it encounters.

Understanding how the system silences invaders opens up opportunities to exploit it. So far, CRISPRs have been found in about half of the bacterial genomes that have been mapped or sequenced and in nearly all sequenced archaeal genomes. Such pervasiveness indicates that an ability to manipulate the CRISPR-Cas system could yield a broad range of applications. For example, using the knowledge that they have obtained in this work, the Terns now envision being able to design new CRISPR RNAs that will take advantage of the system to selectively cleave target RNAs in bacterial cells.

"These could target viruses that wipe out cultures of bacteria used by industry to produce enzymes," said Michael Terns, "or could target the gene products of the bacteria themselves. With this set of Cas proteins, we now know how to cut a target RNA at the site we choose."

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Antibodies

Antibodies are specialized molecules of our immune system that can specifically recognize and neutralize pathogens or foreign substances. Antibody research in biotech and pharma has recognized this natural defense potential and is working intensively to make it therapeutically useful. From monoclonal antibodies used against cancer or autoimmune diseases to antibody-drug conjugates that specifically transport drugs to disease cells - the possibilities are enormous

Topic world Antibodies

Antibodies are specialized molecules of our immune system that can specifically recognize and neutralize pathogens or foreign substances. Antibody research in biotech and pharma has recognized this natural defense potential and is working intensively to make it therapeutically useful. From monoclonal antibodies used against cancer or autoimmune diseases to antibody-drug conjugates that specifically transport drugs to disease cells - the possibilities are enormous