Modified crops reveal hidden cost of resistance

Genetically modified squash plants that are resistant to a debilitating viral disease become more vulnerable to a fatal bacterial infection, according to biologists.

"Cultivated squash is susceptible to a variety of viral diseases and that is a major problem for farmers," said Andrew Stephenson, Penn State professor of biology. "Infected plants grow more slowly and their fruit becomes misshapen."

In the mid-1990s, the U.S. Department of Agriculture approved genetically modified squash, which are resistant to three of the most important viral diseases in cultivated squash. However, while disease-resistant crops have been a boon to commercial farmers, ecologists worry there might be certain hidden costs associated with the modified crops.

"There is concern in the ecological community that, when the transgenes that confer resistance to these viral diseases escape into wild populations, they will (change) those plants," said Stephenson, whose team's findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . "That could impact the biodiversity of plant communities where wild squash are native."

Stephenson and his colleagues James A. Winsor, professor of biology; Matthew J. Ferrari, research associate; and Miruna A. Sasu, doctoral student, all at Penn State; and Daolin Du, visiting professor, Jiangsu University, China, crossed the genetically modified squash into wild squash native to the southwestern United States and examined the resulting flower and fruit production.

Unlike a lab experiment, the researchers tried to mimic a real world setting during their three-year study. The researchers then looked at the effects of the virus-resistant transgenes on prevalence of the three viral diseases, herbivory by cucumber beetles, as well as the occurrence of bacterial wilt disease that is spread by the cucumber beetles.

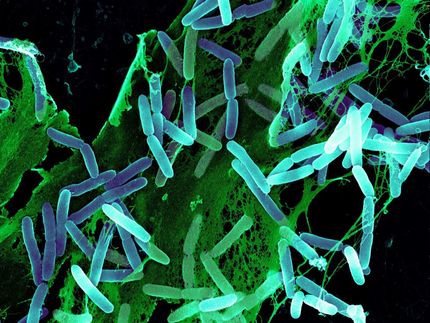

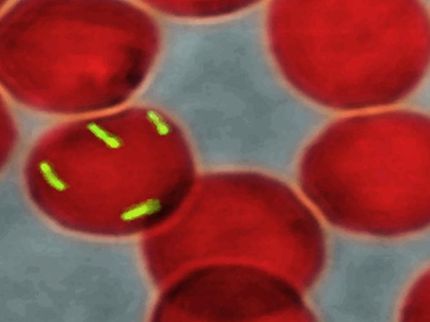

"When the cucumber beetles start to feed on infected plants they pick up the bacteria through their digestive system," explained Sasu. "This feeding creates open wounds on the leaves and when the bugs' feces falls on these open wounds, the bacteria find their way into the plumbing of the plant." The researchers discovered that as the viral infection swept the fields containing both genetically modified and wild crops, the damage from cucumber beetles is greater on the genetically modified plants. The modified plants are therefore more susceptible to the fatal bacterial wilt disease.

"Plants that do not have the virus-resistant transgene get the viral disease," explained Stephenson, whose team's work is funded by the National Science Foundation. "However, since cucumber beetles prefer to feed on healthy plants rather than viral infected plants, the beetles become increasingly concentrated on the healthy - mostly transgenic - plants."

During a viral epidemic, the transgene provides modified plants with a fitness advantage over the wild plants. But when both the bacterial and viral pathogens are present, the beetles tend to avoid the smaller viral infected plants and concentrate on the healthy transgenic plants. This exposes those plants to the bacterial wilt disease against which they have no defense. "Wild and transgenic plants had the same amount of damage from beetles before viral diseases were prevalent in our fields," said Stephenson. "Once the virus infected the wild plants, the transgenic plants had significantly greater damage from the beetles."

Results from the study show that over the course of three years, the prevalence of bacterial wilt disease was significantly greater on transgenic plants than on non-transgenic plants. According to the researchers, their findings suggest that the fitness advantage enjoyed by virus-resistant plants comes at a price. Once the virus infects susceptible plants, cucumber beetles find the genetically modified plants a better source for food and mating.

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.