Trigger of deadly food toxin discovered

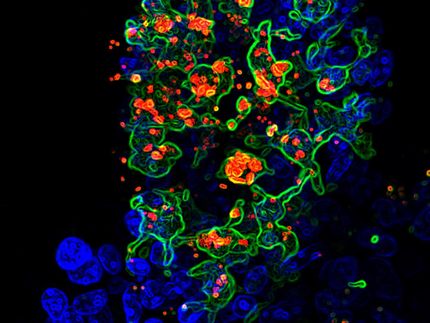

Finding by UCI scientists could help prevent liver cancer

Advertisement

A toxin produced by mold on nuts and grains can cause liver cancer if consumed in large quantities. UC Irvine researchers for the first time have discovered what triggers the toxin to form, which could lead to methods of limiting its production.

Because of lax or nonexistent regulation, 4.5 billion people in developing countries are chronically exposed to vast amounts of this toxin, called aflatoxin – often hundreds of times higher than safe levels. In places such as China, Vietnam and South Africa, the combination of aflatoxin and hepatitis B virus exposure increases the likelihood of liver cancer occurrence by 60 times, and toxin-related cancer causes up to 10 percent of all deaths in those nations.

"It's shocking how profoundly these molds can affect public health," said Sheryl Tsai, UCI molecular biology & biochemistry, chemistry, and pharmaceutical sciences associate professor and lead author of a study in the journal Nature.

Aflatoxin can colonize and contaminate nuts and grains before harvest or during storage. The U.S. Food & Drug Administration considers it an unavoidable food contaminant but sets maximum allowable limits. The toxin wreaks havoc on a cancer-preventing gene in humans called p53. Without p53 protecting the body, aflatoxin can compromise immunity, interfere with metabolism, and cause severe malnutrition and cancer.

Tsai, graduate student Tyler Korman and undergraduate Oliver Kamari-Bidkorpeh, along with Johns Hopkins University researchers, found that a protein called PT is critical for aflatoxin to form in fungi. Previously, scientists didn't know what prompted the toxin's growth.

"The protein PT is the key to making the poison," Tsai said. "With this knowledge, perhaps we could kill the PT with drugs, inhibiting the mold's ability to make aflatoxin."

Destroying the mold – rather than just the PT – is the traditional method of decontamination, but it's expensive, costing hundreds of millions of dollars worldwide.

"This finding will lead to an increased understanding of how aflatoxin causes liver cancer in humans," said Dr. Frank Meyskens, Daniel G. Aldrich Jr. Endowed Chair and director of UCI's Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center. "It should allow for the development of inhibitors and, hopefully, a new chemoprevention approach to this deadly cancer."