McMaster researchers discover a new antibacterial lead

A promising discovery by McMaster University researchers has revealed an ideal starting point to develop new interventions for resistant infections

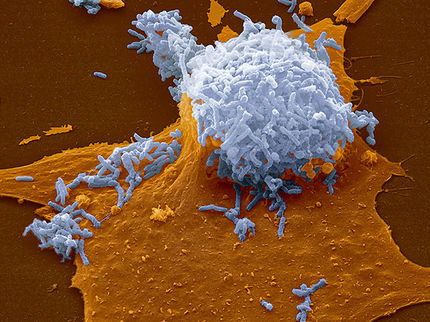

antibiotic resistance has been a significant problem for hospitals and health-care facilities for more than a decade. But despite the need for new treatment options, there have been only two new classes of antibiotics developed in the last 40 years. Now a promising discovery by McMaster University researchers has revealed an ideal starting point to develop new interventions for resistant infections.

Eric Brown, a professor and chair of the Department of Biochemistry and Biomedical Sciences, and a team of researchers from the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research have identified a novel chemical compound that targets drug-resistant bacteria in a different way from existing antibiotics. The discovery could lead to new treatments to overcome antibiotic resistance in certain types of microorganisms. The findings were published in Nature Chemical Biology .

"Everyone reads the headlines about drug-resistant bugs, it's a big problem," said Brown, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Antimicrobial Research. "Really what we're trying to do is understand whether or not there are new ways to tackle this problem."

The research team, which included biochemists and chemists from McMaster University, used high-throughput screening to uncover the new class of chemical. The approach allows scientists to look for small molecules that kill bacteria as well as examine the molecular mechanisms and pathways they exploit.

Existing antibiotics destroy bacteria by blocking production of its cell wall, DNA or protein. The new McMaster-discovered compound, MAC13243, is directed at blocking a particular step in the development of the bacteria's cell surface, which until now has not been recognized as a target for antibiotics.

"We're excited about finding a new probe of a relatively uncharted part of bacterial physiology," Brown said. "It's a new way of thinking about the problem. Who knows, could this chemical become a drug? Anything's possible. But at the very least we've advanced the field and created some tools that people can use now to try to better understand this pathway."

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.