Chemotherapy resistance: Checkpoint protein provides armor against cancer drugs

Cell cycle checkpoints act like molecular tripwires for damaged cells, forcing them to pause and take stock. Leave the tripwire in place for too long, though, and cancer cells will press on regardless, making them resistant to the lethal effects of certain types of chemotherapy, according to researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. Their findings, published in Molecular Cell, help explain how the checkpoint exit is delayed in some cancer cells, helping them to recover and resume dividing after treatment with DNA-damaging cancer drugs.

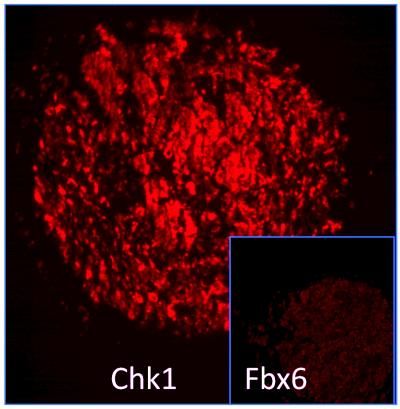

These tumors with low levels of Fbx6 are unable to degrade the checkpoint protein Chk1 making them resistant to certain cancer drugs.

Courtesy of Dr. Youwei Zhang, Case Western Reserve University.

"A lot of progress has been made in understanding the molecular details of checkpoint activation," says senior author Tony Hunter, Ph.D., a professor in the Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory, "but checkpoint termination, which is essential for the resumption of cell cycle progression, is less well understood."

The Salk researchers say that a better understanding of this crucial process may allow them to develop biological markers that predict clinical resistance to chemotherapy and to design cancer drugs with fewer side effects by exploiting the molecular mechanism underlying the checkpoint exit.

"If we could screen tumors for markers of chemo-resistance, we could then adjust the treatment accordingly," hopes first author You-Wei Zhang, Ph.D., formerly a postdoctoral researcher in Hunter's lab and now an assistant professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

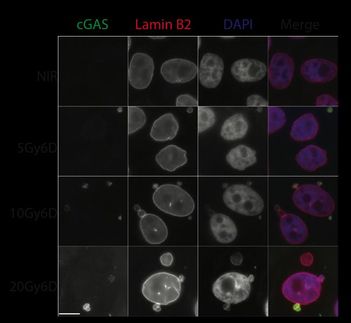

In response to DNA damage and blocked replication — the process that copies DNA — eukaryotes activate the DNA damage checkpoint pathway, which stops the cell cycle, buying time to repair damage and recover from stalled or collapsed replication forks. If not repaired, these errors can either kill a cell when it attempts to divide or lead to genomic instability and eventually cancer.

A key role in this process is played by the checkpoint protein Chk1, which responds to stressful conditions induced by hypoxia, DNA damage – inducing cancer drugs, and irradiation. These same conditions set the protein up for eventual degradation. But how the cellular protein degradation machinery knows that it is time to dispose of activated Chk1 was unclear.

In his experiments, Zhang discovered that activation of Chk1 exposes a so-called degron, a specific string of amino acids that attracts the attention of a protein known as Fbx6, short for F box protein 6. Fbx6 in turn brings in an enzyme complex that flags Chk1 proteins for degradation, allowing the cell to get rid of the activated checkpoint protein. Once Chk1 is eliminated, cells will resume the cell cycle progression, or, in the prolonged presence of replication stress, undergo programmed cell death. Yet some cancer cells keep dividing even in the presence of irreparable damage.

"Camptothecins are FDA-approved cancer drugs that induce replication stress and stop cancer cells dividing, but their clinical antitumor activity is very limited by the relatively rapid emergence of drug resistance, and the mechanisms are poorly understood," says Hunter. "We wondered whether defects in the Chk1 destruction machinery might allow cells to ignore the effects of camptothecin and similar drugs used for chemotherapy."

When Zhang checked cultured cancer cell lines and breast cancer tissue, he found that low levels of Fbx6 predicted high levels of Chk1 and vice versa. But most importantly, he was able to demonstrate that two of the three most camptothecin-resistant cancer cell lines in the cancer cell line panel available through the National Cancer Institute displayed significant defects in camptothecin-induced Chk1 degradation, which seemed to be caused by very low levels of Fbx6 expression.

"Chk1 and Fbx6 clearly play an important role for the regulation of the response to chemotherapy," he says. "One day, they could become an important prognostic marker that predicts patients' responsiveness to drugs such as irinotecan, platinum compounds, and gemcitabine, while Chk1 inhibitors might increase tumor cells' sensitivity to these drugs." Such a combination therapy could overcome clinical resistance or allow doctors to reduce the amount of administered drug, thereby reducing the often debilitating side effects.