Fighting disease atom by atom

Rice lab's atomic map of hepatitis E may reveal strategies to fight it

Advertisement

Researchers at rice University and their international colleagues have for the first time described the atomic structure of the protein shell that carries the genetic code of hepatitis E (HEV). Their findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could mean that new ways to stop the virus may come in the not-too-distant future.

Researchers at Rice University and their international colleagues have for the first time described the atomic structure of the protein shell that carries the genetic code of hepatitis E (HEV).

Rice University

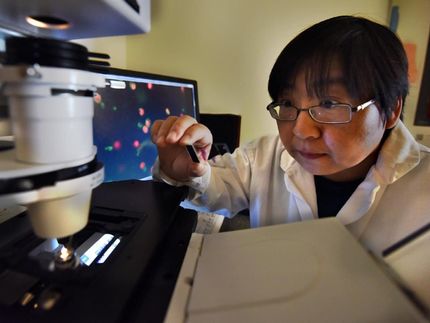

Rice graduate student Tom Guu was part of the research team led by Yizhi Jane Tao, an assistant professor of biochemistry and cell biology. Guu said researchers have had a difficult time analyzing HEV, a particularly nasty form of viral hepatitis that flourishes in the developing world, where poor sanitation is common.

"About 10 years ago, researchers began to describe what the virus looks like," said Guu. "They found protrusions and indentations on its surface. While it looked a bit like a buckyball, or a geodesic dome, researchers were still stuck."

Without a more detailed description of the virus, it has been hard to design drugs to stop it. To do that, you have to look at it very closely, as the Rice team has done.

Tao's lab specializes in X-ray crystallography, a powerful technique that can pinpoint the exact location of every atom in a biomacromolecule or a large biomacromolecular assembly. In this case, the assembly was the viral capsid shell, made from a network of individual capsid proteins from a strain of HEV that had been made in insect cells, then purified and crystallized.

After two years of intense study, Guu calculated the position of each of the approximately 500,000 atoms that make up the capsid, an icosahedron-shaped particle that roughly resembles a buckyball. The resulting 3-D computer model gives researchers the ability to identify the particle's host-cell binding sites, through which HEV spreads.

"Dr. Tao has already identified potential sites on the new model," said Guu. "If we can prove these sites to be correct, labs around the world can start to design drugs, called competitive inhibitors, to interrupt the binding process and prevent the virus from attaching to cell receptors in the first place."

Guu compared the virus's capsid protein to a hollowed-out watermelon. "You have the outer shell of the virus, but you take out its insides," he said. "It retains its outside properties." The empty capsid may still bind to a cell, but it contains no genetic material to transfer, rendering it noninfectious and therefore an excellent candidate for a vaccine.

"In fact, other researchers have used the empty viral shell to vaccinate monkeys, and even humans. Later on, when the researchers challenged them with the real virus, they discovered that prior exposure to this virus-like particle conferred some sort of protection," Guu said.

"This virus has been less studied than others in the pathogenic human virus domain," Tao said. "It has been rather difficult to generate a culture in the lab to study how the virus invades the cell. The only way to work with it is to overexpress the protein on its own."

It took nearly six months for Rice researcher Qiaozhen Ye to identify the right construct, isolate the protein and form the first crystals, after the project was initiated through an international collaboration with Jingqiang Zhang at Sun Yat-sen University in early 2006. Former Rice undergraduate student Douglas Mata then successfully reproduced one of these crystallization conditions. They were surprised to discover that, in the crystallization process, HEV capsid proteins extracted from the cultured cells self-assembled into virus-like particles. This in turn may lead to another strategy: "If you can prevent the protein from assembling, you can stop the virus," Ye said.

Tao sees great potential for their discovery. "There are so many things you can do with the structure that I think it will be useful for many years to come."