Johns Hopkins researchers edit genes in human stem cells

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins School of medicine have successfully edited the genome of human- induced pluripotent stem cells, making possible the future development of patient-specific stem cell therapies. Reporting in Cell Stem Cell , the team altered a gene responsible for causing the rare blood disease paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, or PNH, establishing for the first time a useful system to learn more about the disease.

"To date, only about six genes have been successfully targeted or edited in human stem cells out of countless people and attempts — that's just not efficient enough if we want to move disease research and therapy forward," says Linzhao Cheng, Ph.D., an associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics and member of the Johns Hopkins Institute of Cell Engineering. "We've been able to improve gene targeting and editing in human embryonic stem cells more than 200 fold."

Cheng's lab and collaborators at Johns Hopkins study PNH, a condition where "friendly fire" kills patients' own blood cells and the body can't replenish the lost blood cells due to loss of normal blood stem cells. PNH is an acquired disease that occurs only in adults, according to Cheng. "It's a tough condition to study because we need to study it in blood stem cells and they're difficult to grow in the lab. So for years we've been trying to develop another cell system to better understand and perhaps fix what's going on in PNH." To establish a system for research, they used human embryonic stem cells which can be expanded unlimitedly in the laboratory, but they also had to create a mutation as found in a PNH patient.

To target and remove the function of the one specific gene known to cause PNH, the research team improved on the standard approach of gene targeting, which can remove a functional gene or replace a dysfunctional gene. Gene targeting exploits a cell's own ability to repair broken DNA. When DNA breaks from exposure to mutagens or other agents like DNA-cutting enzymes, DNA-repairing enzymes in the cell find and re-join the two exposed DNA ends. However, if another piece of DNA with exposed ends is floating around, it effectively can be spliced into the broken DNA during repair, and replace the defective copy.

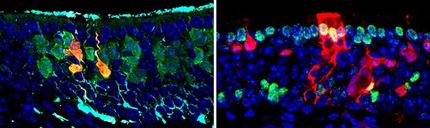

The team's technological improvement includes the use of custom-designed molecular scissors that are made by collaborators at Harvard University and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. These engineered DNA cutting enzymes make a precise break at specific locations in a cell's DNA — in this case in the gene that causes PNH. They added the molecular scissors and a fragment of DNA containing a gene that confers selection of rare targeted clones in both human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. The latter, also known as iPS cells, are very similar to embryonic stem cells in biological properties, but generated by using adult tissues such as skin.

Of all the cells surviving selection, they picked and grew eight iPS cell lines to study further, and five of those contained a targeted insertion at the gene site. Further examination showed that the cells contained the correct number of chromosomes, no longer contained any trace of the molecular scissors and had characteristics as cells from PNH patients that lack a group of cell surface molecules.

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

MicroRNA profiling identifies chemoresistance in small cell lung cancer

How will ‘Pharma 2.0’ fare vs Obama and credit crunch?

Approved lymphoma drug shows promise in early tests against bone cancer