Details of bacterial 'injection' system revealed

Decoded structure of secretion system, essential for infection, could lead to new drugs

Advertisement

New details of the composition and structure of a needlelike protein complex on the surface of certain bacteria may help scientists develop new strategies to thwart infection. The research, conducted in part at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory is published in Nature Structural & molecular biology .

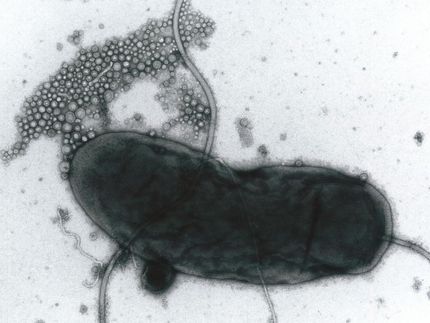

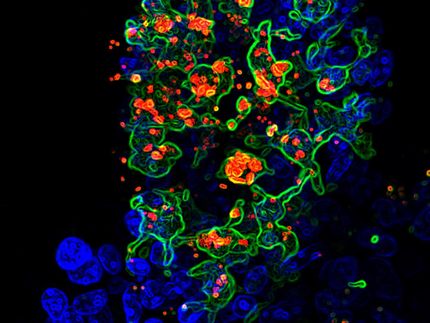

The scientists were studying a needlelike protein complex known as a "type III secretion system," or T3SS, on the surface of Shigella bacteria, a cause of dysentery. The secretion system is a complex protein structure that traverses the bacterial cell membrane and acts as a biological syringe to inject deadly proteins into intestinal cells. These proteins rupture the cell's innards, leading to bloody diarrhea and sometimes death. Similar secretion systems exist in a range of other infectious bacteria, including those that cause typhoid fever, some types of food poisoning, and plague.

"Understanding the 3D structure of these secretion proteins is important for the design of new broad-spectrum strategies to combat bacterial infections," said study co-author Joseph Wall, a biophysicist at Brookhaven Lab.

Previous studies of the type III secretion system have revealed that it is composed of some 25 different kinds of proteins assembled into three major parts: a "bulb" that lies within the bacterial cell, a region spanning the inner and outer bacterial membranes, and a hollow, largely extracellular "needle." But to understand how the parts work together to secrete proteins, the scientists required higher-resolution structural information, and knowledge of the chemical makeup and arrangement of the components.

Using a combination of scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), the scientists have now revealed new details of the "needle complex" structure.

"STEM and the other techniques work in complementary ways," said Wall, who designed and runs the STEM facility at Brookhaven Lab. By itself, STEM cannot reveal a structure, but it gives very accurate sizes of the molecules making up particular parts, which helps scientists hone in on the structure hinted at by the other techniques. STEM also allows only good, intact molecules to be selected for analysis, which avoids errors inherent in bulk measures of mixtures of intact and broken complexes, a problem that may have affected previous analyses.

"Our reconstruction shows an overall size, shape and major sub-component arrangement consistent with previous studies," said Wall. "However, the new structure also reveals details of individual subunits and their angular orientation, which changes direction over the structure's length. We now see 12-fold symmetric features and details of connections between sub-domains both internally and externally throughout the 'needle' base."

The more accurate model therefore shows how the different parts of the injection machine fit together and may fit with other bacterial components that provide the engine to drive injection. These are important steps toward developing a detailed understanding of how the injection machine works, and to developing inhibitors that can prevent bacterial infections.

Although STEM was built more than 25 years ago, it remains a state-of-the-art tool for accurately determining the stoichiometry and homogeneity of biological complexes. It is one of the unique tools that Brookhaven Lab provides to the scientific community.

In the case of this study, said lead author Ariel Blocker of Oxford University and the University of Bristol, UK, "The STEM experiment was key because it provided unique and independent information that allowed the narrowing down of potential symmetries within the structure to a small set of testable possibilities."