To use all functions of this page, please activate cookies in your browser.

my.bionity.com

With an accout for my.bionity.com you can always see everything at a glance – and you can configure your own website and individual newsletter.

- My watch list

- My saved searches

- My saved topics

- My newsletter

Restless legs syndrome

Restless legs syndrome (RLS, Wittmaack-Ekbom's syndrome, or sometimes referred to as Nocturnal myoclonus) is a condition that is characterized by an irresistible urge to move one's legs. It is described as uncontrollable urges to move the limbs to stop uncomfortable or odd sensations in the body, most commonly in the legs, but can also be in the arms and torso. Moving the affected body part modulates the sensations, providing temporary relief. Many doctors express the view that the incidence of restless leg syndrome is exaggerated by manufacturers of drugs used to treat it.[1] Other physicians consider it a real entity that has specific diagnostic criteria. [2] Many people tap their feet or shake their legs resulting from a nervous tic, consumption of stimulants, drug side-effects or other factors; this is usually innocuous, unnoticed, and does not interfere with daily life, quite distinct from restless leg syndrome, which is very different. With a nervous tic, someone does not necessarily notice it, but in RLS it is very noticeable. With a nervous tic, someone may tap their leg or foot, but with RLS they feel an undescribable sensation in their legs that can most closely be compared to a burning, itching sensation in the muscles of the legs or arms.

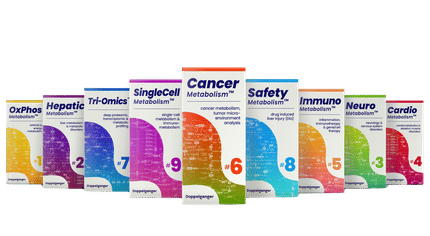

Product highlight

Signs and symptomsThe sensations – and the need to move – may return immediately after ceasing movement, or at a later time. RLS may start at any age, including early childhood, and is a progressive disease for a certain portion of those afflicted, although the symptoms have disappeared permanently in some sufferers. Some experts believe RLS and periodic limb movement disorder are strongly associated with ADHD in some children. Both conditions are hereditary and dopamine is believed to be involved. Many types of medication for the treatment of both conditions affect dopamine levels in the brain. [1]

The sensations are unusual and unlike other common sensations, and those with RLS have a hard time describing them. People use words such as: uncomfortable, antsy, electrical, creeping, painful, itching, pins and needles, pulling, creepy-crawly, ants inside the legs, and many others. The sensation and the urge can occur in any body part; the most cited location is legs, followed by arms. Some people have little or no sensation, yet still have a strong urge to move.

Movement will usually bring immediate relief, however, often only temporary and partial. Walking is most common; however, doing stretches, yoga, biking, or other physical activity may relieve the symptoms. Constant and fast up-and-down movement of the leg, coined "sewing machine legs" by at least one RLS sufferer, is often done to keep the sensations at bay without having to walk. Sometimes a specific type of movement will help a person more than another.

Any type of inactivity involving sitting or lying – reading a book, a plane ride, watching TV or a movie, taking a nap - can trigger the sensations and urge to move. This depends on several factors: the severity of the person’s RLS, the degree of restfulness, the duration of the inactivity, etc.

While some only experience RLS at bedtime and others experience it throughout the day and night, most sufferers experience the worst symptoms in the evening and the least in the morning. NIH criteriaIn 2003, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus panel modified their criteria to include the following:

RLS is either primary or secondary.

CausesCertain medications may worsen RLS in those who already have it, or cause it secondarily. These include: anti-nausea drugs, certain antihistamines (often in over-the-counter cold medications), drugs used to treat depression (both older tricyclics and newer SSRIs), antipsychotic drugs, and certain medications used to control seizures. Hypoglycemia has also been found to worsen RLS symptoms.[4] Opioid detoxification has also recently been associated with provocation of RLS-like symptoms during withdrawal. For those affected, a reduction or elimination in the consumption of simple and refined carbohydrates or starches (for example, sugar, white flour, white rice and white potatoes) or some hard fats, such as those found in beef or biscuits, is recommended. Some doctors believe it is caused by irregular electrical impulses from the brain. Both primary and secondary RLS can be worsened by surgery of any kind, however back surgery or injury can be associated with causing RLS.[5] RLS can worsen in pregnancy. [6] Genetics40% of cases of RLS are familial and are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with variable penetrance. No one knows the exact cause of RLS at present. Research and brain autopsies have implicated both dopaminergic system and iron insufficiency in the substantia nigra (study published in Neurology, 2003).[7] Iron is an essential cofactor for the formation of L-dopa, the precursor of dopamine. An Icelandic study in 2005 confirmed the presence of an RLS susceptibility gene also found previously in a smaller French-Canadian population.[8][9] Various studies suggest chromosome 12q may indicate susceptibility to RLS.[10] There is also some evidence that periodic limb movements in sleep may be associated with the iron-regulating BTBD9 at 6p21.2.[11] Diagnosis

Prevention

TreatmentAn algorithm for treating primary RLS (RLS without any secondary medical condition including iron deficiency, varicose vein, thyroid, etc.) was created by leading RLS researchers at the Mayo Clinic and is endorsed by the Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation. This document provides guidance to both the treating physician and the patient, and includes both nonpharmacological and pharmacological treatments.[12] Treatment of primary RLS should not be considered unless all the secondary medical conditions are ruled out. Drug therapy in RLS is not curative and is known to have significant side effects and needs to be considered with caution. The secondary form of RLS has the potential for cure if the precipitating medical condition (iron deficiency, venous reflux/varicose vein, thyroid, etc.) is managed effectively. Iron supplementsAccording to some guidelines[citation needed], all people with RLS should have their ferritin levels tested; ferritin levels should be at least 50 mcg for those with RLS. Oral iron supplements, taken under a doctor's care, can increase ferritin levels. For some people, increasing ferritin will eliminate or reduce RLS symptoms. A ferritin level of 50 mcg is not sufficient for some sufferers and increasing the level to 80 mcg may greatly reduce symptoms. However, at least 40% of people will not notice any improvement. Treatment with IV iron is being tested at the US Mayo Clinic and Johns Hopkins Hospital. It is dangerous to take iron supplements without first having ferritin levels tested, as many people with RLS do not have low ferritin and taking iron when it is not called for can cause iron overload disorder, potentially a very dangerous condition.[13] PharmaceuticalsFor those whose RLS disrupts or prevents sleep or regular daily activities, medication is often required. Many doctors currently use, and the Mayo Clinic algorithm includes,[12] medication from four categories:

Recently, several major pharmaceutical companies are reported to be marketing drugs without an explicit approval for RLS, which are "off-label" applications for drugs approved for other diseases. The Restless Leg Foundation [15] received 44% of its $1.4 million in funding from these pharmaceutical groups[16] Prognosis

EpidemiologyRestless leg syndrome affects an estimated 2.7% of the general population in the U.S.A., but claims about the prevalence of RLS can be confusing because its severity varies enormously between individual sufferers; only a minority of sufferers experience daily or severe symptoms.[17] Often sufferers think they are the only ones to be afflicted by this peculiar condition and are relieved when they find out that many others also suffer from it. The severity and frequency of the disorder vary tremendously. Many people only experience symptoms when they try to sleep, while others experience symptoms during the day. It is common to experience symptoms on long car rides or during any long period of inactivity (like watching television or a movie, attending a musical or theatrical performance, etc.) Approximately 80-90% of people with RLS also have PLMD, periodic limb movement disorder, which causes slow "jerks" or flexions of the affected body part. These occur during sleep (PLMS = periodic limb movement while sleeping) or while awake (PLMW - periodic limb movement while waking). About 10 percent of adults in North America and Europe may experience RLS symptoms, according to the National Sleep Foundation, which reports that "lower prevalence has been found in India, Japan and Singapore," indicating that ethnic factors, including diet, may play a role in the prevalence of this syndrome.[18] HistoryEarlier studies were done by Thomas Willis (1622-1675) and by Theodor Wittmaack.[19] Another early description of the disease and its symptoms were made by George Miller Beard (1839-1883).[19] In a 1945 publication titled 'Restless Legs', Karl-Axel Ekbom described the disease and presented eight cases used for his studies.[20] As with many diseases with diffuse symptoms, there is controversy among physicians as to whether RLS is a distinct syndrome. The US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke publishes an information sheet [21] characterizing the syndrome but acknowledging it as a difficult diagnosis. Some physicians doubt that RLS actually exists as a legitimate clinical entity, but believe it to be a kind of "catch-all" category, perhaps related to a general heightened sympathetic nervous system (SNS) response that could be caused by any number of physical or emotional factors[citation needed]. Other clinicians associate it with lumbosacral spinal subluxations and life stress.[citation needed] The UK support group for RLS calls itself the "Ekbom support group" and explains that RLS and "Ekbom's Syndrome" are two names for the same condition. However, RLS and delusional parasitosis are entirely different conditions that share part of the Wittmaack-Ekbom syndrome eponym, as both syndromes were described by the same person, Karl-Axel Ekbom. [19] See also

References

Categories: Sleep disorders | Neurological disorders | Syndromes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Restless_legs_syndrome". A list of authors is available in Wikipedia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||